Join me today to meet a Blessed who ended up on the wrong side of a war.

Name: Pere (Peter) Tarrés i Claret

Life: 1905 - 1950

Status: Blessed

Feast: August 31

You can listen to this as a podcast on Apple Podcasts, Pocket Casts, Spotify or right here on Substack. If you prefer video, you can also follow on YouTube and Odysee (unfortunately, videos on Odysee may be slower to update).

In the Spanish Civil War, fought from 1936-1939, the Nationalists battled against the Republicans, and soon they had the country divided between them, with the Republicans in control of the East. Barcelona, in the East of Spain up near the border with France, was a Republican stronghold. There had been a few Nationalists in Barcelona, but their uprising had been quashed by a group that was already active and powerful: the Anarchists.

Anarchists, of course, opposed order and hierarchy. And when they looked at the Church, they saw hierarchy: God over all, the angels and saints over us, church communities under priests, fathers leading their families, and so on. In the chaos of the war, the Republicans in general and Anarchists in particular turned against the Church. By the end of the war, thousands of priests and monks and nuns had been murdered, in the biggest persecution of Christians in European memory.

And yet, if you had inspected the Republican defensive line pulled back after the fighting at the River Ebro, you might have met an officer who was an unapologetic Catholic, quietly preparing for Christmas of 1938 among the Anarchists, and thinking about the absurdity of his situation.

The officer’s name was Pere - the Catalan version of ‘Peter’ - Tarrés i Claret. He hadn’t been born in Barcelona, but nearby, so that for him Barcelona was the big city where opportunities would be found. Peter had been born in 1905, the son of working class parents. His father had worked with machines, and young Peter later said that his enduring image of his father was of the way he looked working a forge, the light of the fire revealing the inner man as he bent iron to his will. Peter would grow up to be, among many other things, a poet.

But for a while, Peter seemed most likely to grow up to be a priest. By about 8 years old he developed a special devotion to the Eucharist. There were local Jesuits, and Peter might have studied with them, but his parents hesitated. He should at least have the option of a secular career. Peter’s father found him a job with a local pharmacist.

Peter turned out to be good with medicines. The pharmacist was impressed. When Peter was old enough, his boss at the pharmacy helped him to get a scholarship, and Peter’s academic career was launched. When Peter did well at school, another scholarship took him to the University of Barcelona. He wanted to be a medical doctor.

Peter’s interest in medicine, however, didn’t reduce his interest in the Church. He approached things as a layman. He became involved with Catholic lay organizations, including Catholic Action but also the Young Christians of Catalonia, FJCC. Spain’s Leftwing political movements suggested that the Church had no answers for the problems faced by workers. Anarchists thought the Church should be abolished altogether. Groups like Catholic Action argued otherwise. Peter had grown up in a working class family, and he wanted to show that the Church had the answers workers were looking for.

In 1927 Peter became Doctor Tarrés. He was still a young man in his early twenties. In the same year, young Doctor Tarrés also came to a decision that would affect the course of his life. After discussion with his spiritual advisor, he decided that he would take a vow of chastity.

Doctor Tarrés set up his medical practice in Barcelona. He soon developed a reputation as someone who would go to see anyone who asked for help. His family remembered one occasion where he had done a house call for a poor woman and come back with the best she could offer for payment: half a dozen fresh eggs. As the years passed, Doctor Tarrés opened up a sanatorium in Barcelona.

Doctor Tarrés became known as a public intellectual, writing in defense of Catholicism. But the thing that really set him apart from other doctors was his way of looking at patients. He shared the perspective of the Knights Hospitaller, who saw medicine as a way of encountering Christ. The sick man was suffering, Doctor Tarrés reasoned, bearing his own cross, which made him an icon of Christ - if only a doctor had eyes to see.

It didn’t take long for this way of doing medicine to be noticed. One day a friend came to visit Doctor Tarrés at his sanatorium. The friend got lost and ended up in a bad part of town, and was mugged. The muggers took all his valuables. As they were leaving, they asked him why he was in their part of town. But when he said he wanted to visit his friend who ran the sanatorium, their approach changed. The muggers gave back everything they had taken and helped the man find his way to Doctor Tarrés.

Doctor Tarrés’ sanatorium was making a difference, but around him things were spinning out of control. Spain was in political turmoil, and various factions on the Left and on the Right claimed to have the answers. In Barcelona, the Anarchists were already vocal. They had been in Spain since around the turn of the 20th century. They had already figured out that their message was not going to be conveyed by peaceful persuasion or even peaceful labour strikes, and so for the last few decades they had been engaging in what they called ‘propaganda of the deed’, what their heirs today would call ‘direct action’: violent riots, criminal activity, intimidation and outright terrorism.

In 1936 Spain exploded into civil war. The Anarchists rose along with everyone else, especially in Barcelona, and they soon became a powerful force among the Leftist defenders of the Spanish Republic, attending meetings armed and with bandoliers of bullets slung over their shoulders. The Spanish Republicans did little to halt the persecution of Catholics. The historian Julio de la Cueva reports that by the end of the war, the dead included 4172 diocesan priests and priests in training, 2364 monks and friars, 283 nuns and 15 bishops. Afterward, people would be amazed at the ferocity of the persecution. Republicans stuffed rosary beads into the ears of monks until they were deafened, or choked Catholics with crucifixes. In Barcelona, the bodies of nuns were dug up and put on display for the entertainment of the masses. The anti-Christian sentiment ran so deep that it affected ordinary language, with many dropping the traditional goodbye, adios, literally a commendation of the other person to God, in favour of the neutral salud.

Doctor Tarrés missed the outbreak of the war because he was at a retreat, at the nearby monastery of Montserrat. He got back to find the Nationalists crushed and the Republicans in control. Suddenly Doctor Tarrés had to be an advocate for the Catholics in the region. He tried to get the police to protect the monastery at Montserrat - a difficult task since while many police wanted to help, the far Left was arguing that a police force should not be politically neutral. Doctor Tarrés became an extraordinary minister for the Eucharist, bringing it to Catholics when priests could not safely move through the city. As time passed, Tarrés himself became a target, and the police searched his house. He spoke to his family about the chance of martyrdom, and he welcomed the possibility. But the government summons, when it came, was not what he expected.

He was being drafted.

The army had put out a call for doctors. There were many doctors in the region of Barcelona, but only a handful even showed up. Doctor Tarrés was one of them. His Division had many Anarchists in it, so in a way he was putting himself in danger. But then again, Jesus had died for His enemies. Couldn’t Doctor Tarrés at least heal his? In the military, the new field doctor made absolutely no secret of his Catholicism. This was dangerous enough. But then Doctor Tarrés reached a decision. If he survived the war and wasn’t martyred by his own side, he was going to become a priest. He started taking his study materials with him, reading philosophy and brushing up his Latin in his free time. And oddly enough, the fact that Doctor Tarrés was a defiant Catholic had the effect of making him popular. He was soon promoted to the rank of Captain.

And so it was that on Christmas Eve of 1938, Captain Tarrés found himself eating undercooked lentils and thinking about the absurdity of his situation. The lentils were nothing new - a few years under Communists and Anarchists had already collapsed the Republic’s ability to supply its soldiers, so lentils were a standard ration. People joked that the little flat legumes were ‘victory pills’. No, what was absurd was that Tarrés was fighting alongside people who hated Catholic Spain. And even more absurd, he reflected, this ridiculous war had caused everyone to ignore the feast marking the the Incarnation of God. Christmas often reminded him of childhood, but looked at this way, he and his fellow soldiers seemed childish, missing the most important things. And so, with these reflections, Captain Tarrés wandered out of the camp to hold his own private Christmas Vigil under the unchanging stars.

That Christmas would prove to be the last one Captain Tarrés would spend in uniform. Soon afterward the Republicans were forced back. Tarrés was released, sent back to Barcelona where he awaited the fall of the Spanish Republic. In his War Diary, he felt sorry for the Anarchists as the last of them were mopped up by the triumphant Nationalists: “May God have mercy on them.” But Tarrés own sympathies were clear: “¡Viva Cristo Rey! (Long live Christ the King!)” and “Long live Christian Spain!”

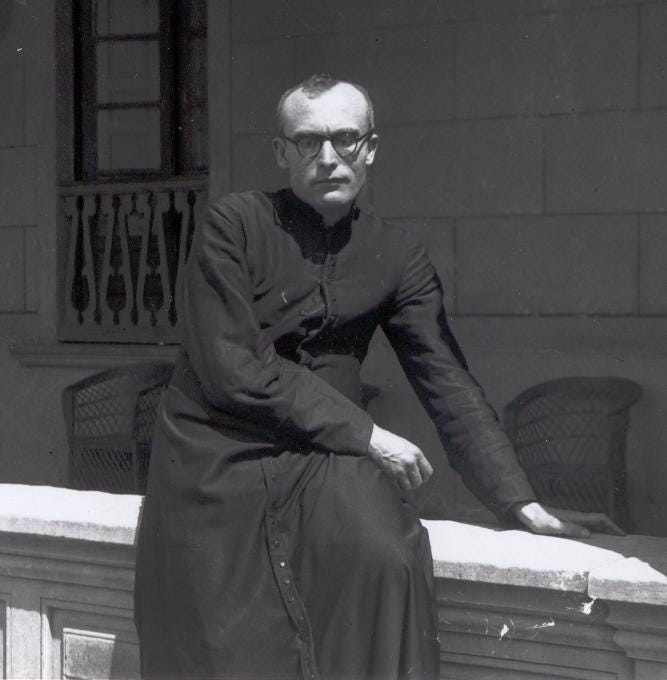

The war was over. Doctor Tarrés helped in the rebuilding effort, and he began to put into action the plan he had made while he was on the front. He was going to become a priest. He began to study. By 1942 he became Father Tarrés. Thousands of priests had been murdered in Spain, and so Father Tarrés was stepping into a Church that desperately needed men who could take leadership positions. The Bishop made him do additional studies in theology, but also put Father Tarrés to work.

And so, as Spain healed while Europe fought the Second World War, Father Tarrés was given task after task. Sometimes he was rebuilding the Catholic lay organization which had been so active during the war, Catholic Action. He helped to rebuild the Benedictine order of Montserrat, which he had tried to protect. And in the city of Barcelona, he continued to practice medicine. He built another clinic. And even though he was always busy, always overworked, Tarrés continued to write, producing poetry as well as other works. When people worried that Father Tarrés was doing too much, he told them that he felt as though he had dived into the ocean. Yes, the work of a priest was this vast thing around him, like the sea, but it was refreshing too, and everything somehow fit together.

By 1945, as the war in Europe came to an end and Father Tarrés turned 40, he was settling back into life as one of Barcelona’s public figures, priest, doctor, writer, poet. And as the world recovered from austerity and as economies returned to peacetime production, he had every expectation of becoming one of Europe’s leading voices.

But then, in 1950, Father Tarrés began to feel sick. One of his colleagues ran some tests. Father Tarrés had lymphoblastic lymphoma - a rare, aggressive form of cancer. His colleague was so shaken by the diagnosis that he bungled the discussion, and Father Tarrés found himself comforting the other doctor about his own bad news. They both knew that the chance of recovery was almost zero.

And so Father Tarrés became a patient in the clinic that he had built. He was 45 years old, and he was dying. But Father Tarrés was not troubled by the diagnosis. He showed up in the hospital with a briefcase, telling his friends that he was reporting for God’s next job for him: being a sick man. He had thought a lot about the suffering of the sick. Now he wanted to do it well. The briefcase he had brought contained just one item, a little statue of Our Lady which he put beside his bed. And then Blessed Pere Tarrés put what was left of his energy into this last assignment, dying well, and before the city of Barcelona could quite process the news, he was gone.

If you enjoy the Manly Saints Project, please consider signing up for a subscription on Substack, or click here or on the logo below to buy me a beer.

What an absolutely amazing story. Every single Saint or Blessed individual I learn about makes me ever more fervent in our faith. I had no idea so many religious were murdered and not long ago - we see what is happening in Nigeria, but for a different reason (yet is it really? I don't think so - I see two opposing forces at play in this world on the macro scale and if you're not with one, you're with the other). In my later years, I am finally taking up learning more about history. So glad I found you here. Great work. God Speed. Adios. I will never here that word the same or look at a lentil again the same (I eat them all the time). It'll be a pleasant reminder of Fr. Tarres.

I enjoyed this story, thanks for sharing Hugh. You are a clear writer with moving prose.