Join me today to meet a blessed who served with the Knights Hospitaller.

Name: Gerard of Villamagna, Gerard Mercatti

Life: c. 1174 - 1245

Status: Blessed

Feast: May 13, May 18

You can listen to this as a podcast on Apple Podcasts, Pocket Casts, Spotify or right here on Substack. If you prefer video, you can also follow on YouTube and Odysee (unfortunately, videos may be slower to update).

When Gerard was a boy of around 12 years old his world fell apart. The disaster that changed the course of his life coincided with a disaster that changed Christendom. From far away, in the Holy Land, came the terrible news of the slaughter at the Horns of Hattin. Meanwhile, Gerard’s family died, leaving the boy completely alone.

Gerard’s world had been upended by a plague. The disease had ripped through his little village of Villamagna, near modern Florence in the Northwest of Italy. The plague killed everyone who cared about Gerard. He was now an orphan.

And after this, Gerard might have slipped through the cracks of his society, but for a strange twist of fate. The lord of those parts, a member of a powerful Florentine clan, came to inspect the village after the plague. And when he saw young Gerard, the lord decided he could find a use for this quiet, thoughtful boy. Our sources hint that the lord had a son who was close to Gerard’s age. The young aristocrat could use a servant, companion, and perhaps one day even a friend.

For Gerard, this meant leaving behind the only place he had ever known and travelling to the big city of Florence. Gerard had probably been preparing to spend his life in agriculture. Suddenly he had to attend school with his young master. And schooling didn’t just involve learning how to read.

Most of all, Gerard would have to learn the ways of war.

Aristocrats in the Middle Ages trained for war. They were training to become knights: mounted warriors with a deep knowledge of tactics and martial arts. They would train through their entire childhoods, and by the end a single knight would ride confidently into battle against massive odds. At 12, Gerard had to catch up. I have to imagine that his training consisted of being knocked down and beaten again and again, getting up every time, until the day when Gerard finally learned how to stand and fight back.

As Gerard moved into his teenage years, he was a servant, a student, and an aspiring warrior. He grew closer and closer to the young lord, for they had something in common. Both of them had a lively faith. Both had listened listened with grief to the tales of the Horns of Hattin. And it seems that, from a young age, both of them had decided that when they grew up, they wanted to be part of the solution. Gerard and his young master began to see their future in the Order of Knights of the Hospital of Saint John of Jerusalem, better known today as the Knights Hospitaller.

The Knights Hospitaller took their name from a hospital. According to the knights, they were merely the latest custodians of this ancient place of healing in Jerusalem. The knights believed the hospital had been old when Jesus was born, and that it had sheltered Mary during the difficult days after Christ’s crucifixion. They were at least correct that the hospital predated the crusades. Even before Christians captured Jerusalem, there were Christians working in the hospital. They turned no one away, and Christians and Muslims alike found healing there. Sick pilgrims and poor locals came to the hospital when they had nowhere else to go. Once in the hospital they were treated with respect and even reverence. The Hospitallers called their patients ‘lords’. It wasn’t that they were sentimental. The core idea of the Hospital was to look at the poor and the sick and recognize in them the face of Christ.

Soon after the capture of Jerusalem during the first crusade, the servants of the Hospital had realized that Christian pilgrims required protection as well as healing. Originally they had hired mercenary knights as guards to protect the Hospital and to escort needy pilgrims to their doors. But the knights had not fit well into the Hospital’s command structure. So under Blessed Raymond du Puy, the Hospitallers had decided to imitate the structure of the Poor Fellow-Soldiers of Christ and of the Temple of Solomon, better known as the Knights Templar. Henceforward the Hospitallers would still have priests and brothers who only served in the Hospital. But they would also open their ranks to fighting men who were willing to become warrior monks.

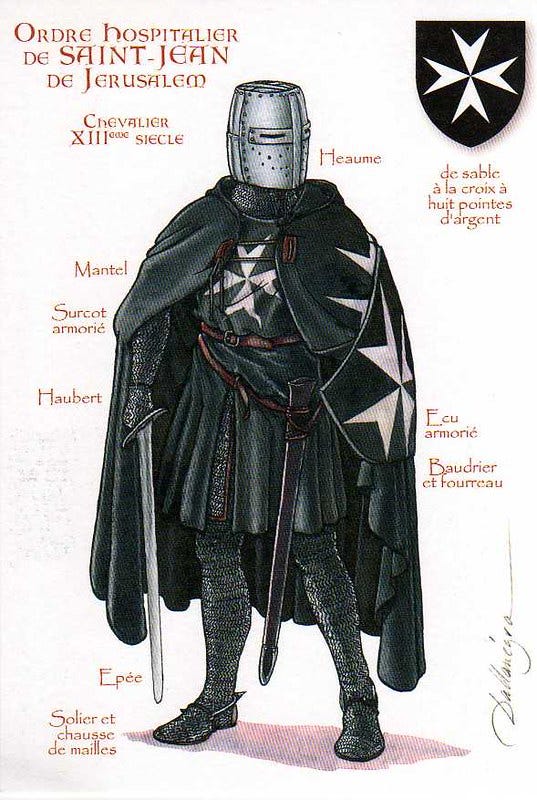

These knights Hospitaller would swear lifelong poverty, using simple armour and plain weaponry. They would swear chastity, living together as brothers. And they would swear obedience, serving the Grandmaster of the order and the masters under him, riding fearlessly out to face the enemies of Christendom in a simple black cloak marked with a white cross.

As Saint Thomas Aquinas saw it, the military orders fulfilled an essential function. Just as Christendom needed the Dominicans to preach, it needed the Hospitallers and the Templars and the other military orders to defend Christians who would otherwise be unable to defend themselves. The need was so great that the Hospitallers began to expand, and soon they were all over Christendom, protecting pilgrims as they travelled East, and holding the line against the armies of Islam in fortresses in Spain and in the Holy Land. Things were going well, and for a while it seemed as though nothing could stop them.

And then came the Horns of Hattin.

In truth, for the Hospitallers, the problem had begun the year before with the death of their grandmaster. He and one of his senior officers had been with a small force of knights destroyed by a much larger Muslim force. This had left the Hospitallers without senior leadership at a key moment.

Back then the Holy Land had largely been under Christian control. But the Christians were about to face their greatest challenge. He was subtle and well-educated, a master of propaganda and a true warrior. These qualities had let him crawl over bodies to become Sultan of Egypt and Syria. His name was Salah al-Din Yusuf ibn Ayyub, or as we remember him, Saladin.

When Saladin took on the Christians, he brought a massive army of 12,000 men. But the Christian lords were not helpless. The King of Jerusalem rode out with 1200 full knights, Hospitallers and Templars among them, perhaps 4000 mounted warriors who were not full knights, called sergeants, and several thousand more footsoldiers and archers. The army marched with a relic of the True Cross. But the foolish King of Jerusalem let himself be lured out into the desert onto the waterless plain below the twin peaks of a dormant volcano that loomed on the horizon like a pair of horns: the Horns of Hattin.

Out in the desert, the Christian army ran out of water. The day ended, and they had no choice but to camp, trying to make do without liquid. That night, Saladin’s men burned the dry grass around them, sending waves of smoke into the Christian camp to make them even thirstier. In the morning, both armies lined up to fight. But the Christians were exhausted before the battle had even begun. And there, under the Horns of Hattin, the Christian forces were annihilated.

The military orders were all but crushed. Saladin had ordered that any Templar or Hospitaller captured should be executed. Without their defence, the cities of the Holy Land were falling. The Master of the Hospitallers in Italy got the bad news in a letter from one of his knights.

Moreover, so great is the multitude of the Saracens and Turks that from Tyre, which they are besieging, they cover the face of the earth as far as Jerusalem, like an innumerable army of ants, and unless aid is quickly brought to the remaining […] cities and to the very few Christians remaining in the East, by a similar fortune they will be plundered by the raging infidels, thirsting for the blood of the Christians. (Dana C. Munro translation)

However, even as Europe reeled from the terrible tidings, for many boys in Europe, the stories of disaster in the Holy Land kindled a fire within. They knew that the Holy Land needed knights, and they might become those knights. And that is why, as soon as they were old enough, the young aristocrat and his servant Gerard joined a local branch of the Knights Hospitaller. Most of the time, only aristocrats were eligible to become brother knights. Gerard joined as a sergeant, a warrior who fought with the knights but remained a layman. And so it was that Gerard, a young peasant who probably expected never to go more than a few miles from his hometown, found himself on the way to distant Palestine to help the poor and sick and face the enemies of Christendom.

We don’t know exactly what role Gerard and his young master fulfilled. They must have helped the sick. They probably rode with pilgrims, leading them through the dangerous paths to the holy places of Palestine. They may have taken part in the Third Crusade, when Christendom found a commander who was a match for Saladin in the King of England, Richard the Lionheart.

And at some point, both Gerard and the young lord were captured.

As Hospitallers, Gerard and his master probably expected to be executed. But after Saladin’s conquest, the Hospitallers were not so feared as they once had been. After some time in captivity, Gerard and his master were ransomed. The experience had left scars. The young noble got sick and died. Gerard was now alone in the Holy Land.

Gerard was a man with two loyalties, and it seems that he wasn’t entirely sure which one to follow. He owed the Order something, although he was still a layman, and so not bound by oaths of obedience, though he would wear their black cloak for the rest of his life. Gerard also owed a lot to the family who had taken him in, back in Florence. He tried to satisfy both debts. Gerard stayed in Jerusalem for several years, working and praying. Then he travelled back to Italy to return to the family in Florence that had made him what he was.

It turned out that Gerard had come back just in time.

For by the time Gerard returned to Florence, a new young lord had grown up among the family who had taken Gerard in. He seems to have been a more worldly man than Gerard’s former master and friend. This lord was going East to seek his fortune. The Christians were finally pushing back against Islam. If he played his cards right, the lord might acquire an estate in the East. And to that end, he was bringing 20 warriors along with him. The lord asked Gerard to come along.

Gerard agreed.

It seems that the Italian force marched boldly along and took ship for the Holy Land. But when they got close, they were attacked by pirates. There were fewer than two dozen Italians, and the pirates numbered about a hundred. The young lord and his men began to panic, running around the ship and wondering whether there was some way to escape. The only man to keep his cool was Gerard, who knelt in the middle of the ship, apparently lost in prayer as projectiles flew around him. And then, when the pirates began to board, Gerard drew his sword and joined the fight. He was a Hospitaller, and being outnumbered only five to one would make for a pleasant enough fight.

Watching Gerard charge into battle encouraged the men, who joined him in the fight. By the time the pirates disengaged, about half of them were dead. The Christian party had won. And they had also found a new respect for the quiet Hospitaller.

Gerard would end up spending the next few years in the Holy Land. It was a strange time. Christians should have been regaining the lands they had lost. But most of the time, they were fighting each other instead. That only helped men like Gerard stand out. Quiet and prayerful, a whirlwind of destruction in battle, Gerard began to acquire a reputation among the Christians. And this recognition made Gerard deeply uncomfortable. He had never wanted fame or glory.

He had now been in the Holy Land for seven years. Gerard began to sense God calling him elsewhere, though it seems he wasn’t quite sure what God wanted him to do. And so Gerard took ship back to Florence.

It wasn’t an easy trip. The ship was caught in a storm, though once again, those on board drew comfort from the Hospitaller who knelt in the middle of the deck in prayer as the ship rolled in the waves. The storm passed, and then the ship was sailing into harbour in Tuscany.

When Gerard disembarked, he realized why he had been drawn back to this place. Saint Francis of Assisi was in town. The two men had a long conversation. By the end, Gerard knew what he was going to do. And Saint Francis had given him a gift: the grey robe of a Franciscan. Gerard would wear it, under his Hospitaller’s cloak, for the rest of his life.

Gerard returned to the place he had been born. He would be a hermit. His life became one of self denial, of fasting and prayer. He also became notoriously difficult to find. He would appear at church, then fade into the woods to think and pray in silence and solitude. Every once in a while, someone would catch a glimpse of him out there. One man swore that he had seen the old warrior in what should have been a darkened forest, only it wasn’t dark, and the light was pouring out of Gerard himself.

Those who did manage to track Gerard down often asked for his help, for healing or judgement or just advice. He healed a young boy who had fallen off a balcony and broken his skull on the stones below. On one occasion, Gerard was passing by a woman who had been haunted by a secret sin for a decade. Something had made her unable to confess it. Gerard gently spoke to her about the secret she had never mentioned to anybody, and when she went to confess, she found she was finally able to let it go.

By the time he was an old man, the orphan from Villamagna had become famous twice, first as a warrior, then as a hermit. Now Gerard was frail, and he entered a hospital himself, being nursed by local nuns. And it was at this time that such an odd thing happened that it became forever part of the symbolism surrounding Blessed Gerard.

One night, after checking in on the very old, very frail Gerard, a nun asked whether he wanted anything else. Gerard told her that he would love a few cherries. But it was January, so of course there were no cherries to be had. The nun went away, thinking that the old man’s mind was wandering. But then, some impulse made her go outside and just look at the cherry tree nearby. And when she arrived, she found that through some strange grace, some private miracle, the branches were heavy with unseasonable fruit. She didn’t know what to make of it, and so she just brought a branch back to the old man in the bed. And that is why, if you see a painting of a man dressed for war, wearing the cloak of the Knights Hospitaller but rather incongruously holding a branch of cherries, it is a memorial of Blessed Gerard of Villamagna.

If you enjoy the Manly Saints Project, please consider signing up for a subscription on Substack, or click here or on the logo below to buy me a beer.