Join me today to meet the warrior saint who fell from power.

Name: Theophilus, Theophilus of Cyprus, Theophilus the Younger, Theophilus the Martyr

Life: died around 790 AD

Status: Saint

Feast: July 22, January 30

You can listen to this as a podcast on Apple Podcasts, Pocket Casts, Spotify or right here on Substack. If you prefer video, you can also follow on YouTube and Odysee (unfortunately, videos on Odysee may be slower to update).

In the last decades of the 7th century AD, an eerie rainbow hung over Constantinople, modern Istanbul. It seemed a bad omen, and according to the chronicler Theophanes, “all mankind shuddered. Everyone said it was the end of the world.” (Turtledove translation). The reason for the fear among the Byzantines, the citizens of the Eastern Roman Empire, went beyond the sign in the sky. Over the past forty years, Islam had gone from a local religion to a world empire, swallowing up the Persian empire and defeating the armies of the Byzantines. The buffer states that should have protected the city of Constantinople had fallen. The Byzantines had reacted by reorganizing on a more military model, setting up the Themes, regional blocks in which armies were stationed under the direct command of a single appointed strategos, who could act quickly and independently. But the Themes only slowed the Muslim advance. Now, as the strange rainbow lingered over the city, news had arrived that a vast Muslim fleet was sailing North, headed for Constantinople.

At first, the Muslims threw the Byzantines back, as they had so often before. But the emperor had one last card to play. Some time before, a man had arrived in Constantinople, fleeing the Islamic conquest of Egypt. The man’s name was Kallinikos, and he was an inventor. He had put his mind to developing a weapon to get revenge on the people who had driven him from his home, and he had presented his invention to the emperor in Constantinople.

And so it was that in the fateful naval battle before Constantinople, the Byzantine ships were equipped with something the Muslims did not understand. Metallic tubes extended from the prow and sometimes the sides of the Byzantine ships. And when they came close to the Muslim fleet, these tubes began to shoot fire.

The chronicler Theophanes called the substance ‘sea fire’, and others called it liquid fire. Kallinikos’ invention had two parts. First, he had devised a chemical formula for fire in a jar, a chemical that once ignited burned what it touched and could not be extinguished by water. Kallinikos had combined this invention with the ancient fire-fighting technology of the water siphon. Kallinikos’ invention was built to spray the chemical, and ignite it as it left the siphon. Kallinikos had invented a flamethrower.

The fire siphon changed the face of naval warfare. Now, in the desperate fight in front of Constantinople, Muslim ships burned. Men burned. The water burned under a layer of sea fire, and nothing seemed able to put it out. Constantinople was saved.

The introduction of the secret substance that came to be called ‘Greek fire’ gave Byzantine ships a new edge in combat. It was an edge they desperately needed. After the failed Islamic siege of Constantinople, Byzantine power gradually returned, at least a little. Byzantine fleets were now equipped with Kallinikos’ siphons and pre-made jars of Greek Fire. (The recipe itself was a state secret.) The fleets used Greek fire against the Muslims, against the migrating Slavs, and against the Northmen who settled at Kiev and became known as the Rus - although the Norse hero Yngvarr did boast that he defeated a Byzantine fire ship by lighting a fire arrow and shooting it directly into the muzzle of a siphon, causing the ship to explode.

One area where Greek fire was especially useful was in the Theme, or military region, of the Cibyrrhaeots. The Theme was named after the Greek city Cibyra, but the Theme’s actual capital and the headquarters of the strategos was Attaleia, modern Antalya in Southwest Turkey. The city was on the coast of the Mediterranean, and the territory of Theme extended along the coast - which was part of what made the Theme of the Cibyrrhaeots unusual. In most Themes, the strategos was a general who primarily commanded a land army. But in the Theme of the Cibyrrhaeots, the local strategos was an admiral. This strategos commanded a fleet, armed with the latest developments in Byzantine naval technology, and poised to intervene anywhere in the Eastern Mediterranean. This was the naval strikeforce of the Byzantine Empire.

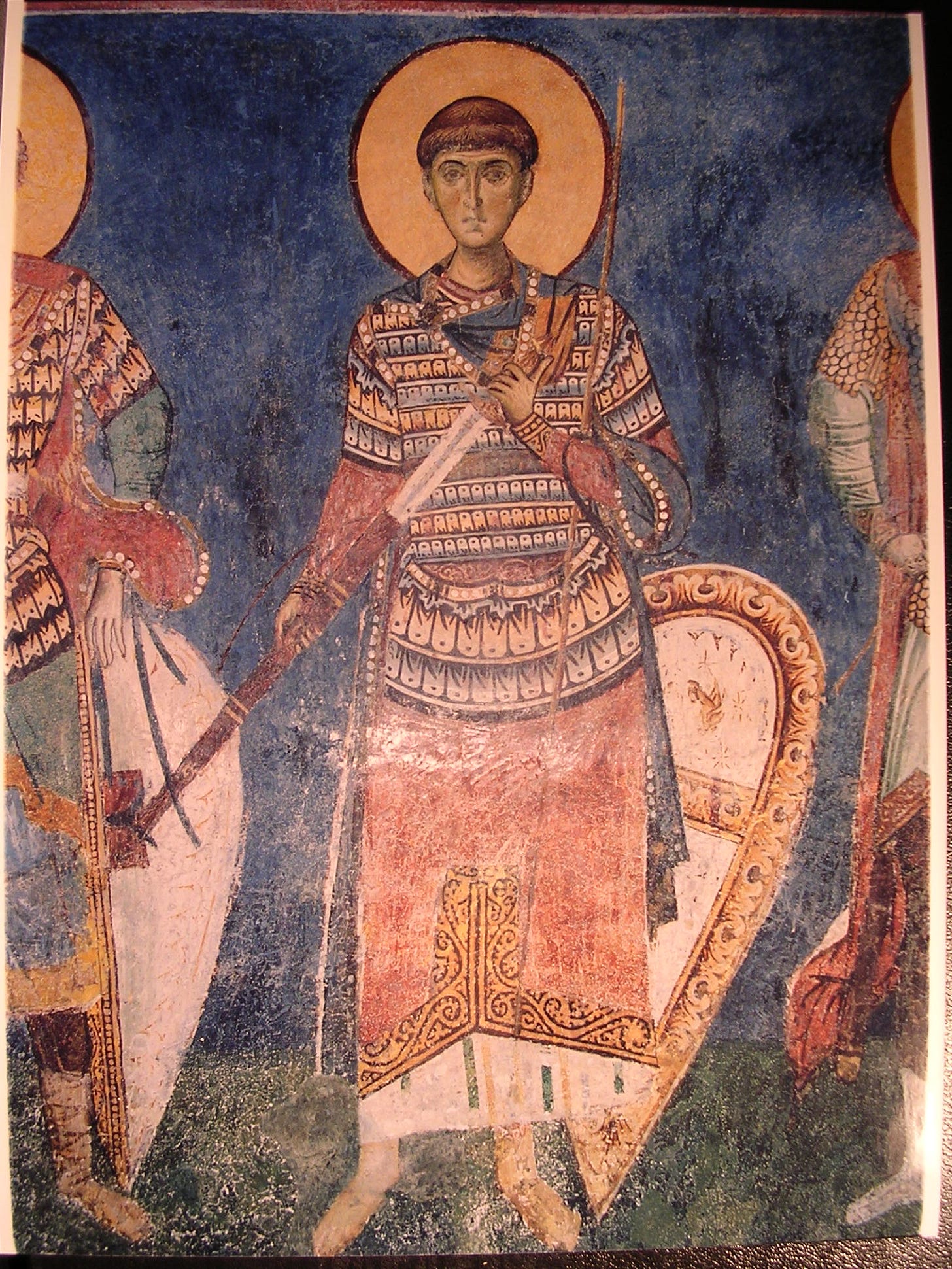

As the 8th century reached its end, the man serving as strategos in the Theme of the Cibyrrhaeots was Theophilus. He was a native of Constantinople, from one of the noble families of the city. Theophilus was the sort of man the Byzantines needed if they were to have any hope of holding the empire together: well built and strong, and a skillful commander. Theophilus may well have been a rising star. Naval command was not as prestigious as a land command, so if he did well he might be promoted.

When Theophilus considered the Christian world as a whole, he probably saw grounds for optimism. In the West, the Emperor Charles the Great was reforging the Western Roman Empire, only this time it would be the Holy Roman Empire. Charles’ ancestors had crushed the Muslim invasion of France, and secured Christian lands in Western Europe. But in the East, things were not going well. The Byzantines were being pushed back by the powerful Caliph Harun al-Rashid. It had started in the 780s, when Harun was only the crown prince. Back then, Harun had plundered so much treasure that he had almost crashed his own economy. Now the Byzantines were paying vast tribute to maintain an uneasy truce.

The Byzantines were also divided over the question of icons. For centuries, Christians had venerated icons. But in the 8th century, a critique of this practice had arisen inside the Church. Critics argued that Christians weren’t venerating icons, they were worshipping them. It was a timely argument, since Muslims accused Christians of the same thing. The critique provoked a violent upheaval in the Church: devotions and traditions that had existed for centuries were thrown away in an effort to break with the past. We remember the men, like Saint Joannicius the Great and Saint John of Damascus, who stood up against this destruction of tradition. The debate only became more violent when emperors and soldiers got involved. The late emperor had been opposed to icons, an iconoclast, but when he died it became apparent that his widow, the Empress Irene, had secretly disagreed. Now Irene was defending icons - and this polarized the military. Entire units were so dedicated to icon hating that they deserted the empire and joined the Muslims.

Empress Irene was barely keeping her empire together when the imperial spies in the Caliphate sent a message to Constantinople. Cyprus was in danger again. Cyprus had been lost and regained and lost again. Now Cyprus was theoretically neutral, or rather it belonged to both the Muslims and the Christians. But it seemed that the Caliph wanted the island all to himself. Caliph Harun al-Rashid was preparing a fleet to annex Cyprus.

The Empress Irene considered the intelligence report, and sent messengers South, to the Theme of the Cibyrrhaeots. And so it was that the strategos Theophilus rallied the Byzantine fleet in the harbour of Attaleia, and sailed South, toward Cyprus.

Byzantine fleets usually travelled with two lines of scout ships before them, so that the first line of scouts could pass the news to the second, and the second could pass it back to the fleet, using smoke signals or the complex code of the white signalling flag. Soon the scouts were sending good news. They had come upon the Muslim fleet, sailing North of Cyprus. The Muslims were completely unaware that they were being hunted. It was a nice clear day, and the Muslims had let their fleet spread out, which meant that they were scattered and vulnerable. It was the kind of scenario that naval officers read about in textbooks: this was the moment to attack.

Theophilus must have prepared his men. The Byzantine fleet would have tightened up their own formation, moving into a crescent shape with big ships on the crescent’s points and the flagship of Theophilus in the middle. Ships no longer rammed each other - at least not on purpose - so the crescent would surge forward and try to surround as many Muslim ships as possible, then squeeze in, chop off their oars to immobilize them, and burn the ships, or board them and capture the crew. Now, as the Byzantines descended on the Muslim fleet, there were preparations to be made. Marines put on their elaborate cataphract armour. Archers slid into more flexible, padded garments. Ballista crews cranked the mechanisms of the big deck-mounted crossbows, drawing back the silk-reinforced cords and preparing their supplies of mice and flies - the sailors’ nicknames for the bolts that would soon be whipping along the enemy deck. The crews prepared the fire siphons and cranes.

Theophilus may have had time to speak to his senior officers. Our texts suggest there were senior officers, though it is not clear how many. Theophilus explained his plan: the Muslim fleet was planning a surprise attack on Cyprus, but this would be a surprise attack on them. The Byzantines would attack those who were caught, and scatter the rest. The message to the Caliph would be clear. If Theophilus was following the naval manuals of the day, he would have encouraged his men, telling them that their fear was understandable, but victory and glory were within reach, if only they would stand together. He would have promised to fight alongside them. The meeting would have ended in prayer, and then Theophilus’ senior men would have returned to their ships.

And so the textbook operation began to play itself out. The crescent of Byzantine ships advanced toward a disorganized group of Muslim ships, with mice and flies whipping out from the front-mounted ballistae of the Byzantines into the surprised and panicked Muslim crews. The disorganized Muslims would have been scrambling to get ready, to get their marines in armour and prepare the sand, and the pots of vinegar or aged urine which had proved the only things that could put out Greek fire.

Then Theophilus gave the order to advance. Perhaps by now the ships were close enough to use trumpets to send the signal, although probably with all the shouting of preparation it was sent with the white signalling flag. And then… nothing happened. Theophilus noticed that no ship wanted to be the first to charge the Muslim fleet.

This was also covered in the naval manuals. And the manuals were clear: when every ship was afraid to be the first in, the fleet needed to see the courage of their commander. And so Theophilus shouted orders to the captain of his flagship, and the soldiers at the oars pulled forward, and the flagship of the Theme of the Cibyrrhaeots surged out to battle.

Theophilus’ ship was already far out from his fleet when it became clear that no one was moving. The flagship hit the Muslim fleet alone. What had gone wrong?

One of our sources, the chronicler Theophanes, explains that Theophilus had gotten too far ahead of his men. These things happened to commanders who were inexperienced. But Theophanes adds a curious detail, underlining the fact that Theophilus was not inexperienced, that he was good at his job. And so Theophanes hints at something that other sources make explicit, which is that Theophilus was betrayed. His junior commanders had their own plans. Perhaps they were ambitious, and were willing to sacrifice the battle for their own chance at command. They knew that Theophilus was the kind of commander to lead by personal courage, and they had planned for it.

And so the flagship of the Cibyrrhaeots found itself alone, surrounded by Muslim ships. Theophilus, at least, would not go easily. The flagship prepared the fire siphons, as archers fired at the Muslim ships around them. And yet, no matter how well Theophilus’ ship was piloted, it could not be positioned against every ship at once. It would not have been long before a Muslim ship slid by and sliced off the oars from the flagship, leaving the fship unable to manoeuvre. The Muslims used iron poles with hooks on the end to grab the flagship and pull in close. Then it would have been down to hand-to-hand fighting. The Byzantine archers and marines knew the stakes and would have fought hard. The fire siphons would have roared flame, and perhaps there was even time to use the cranes that swung outward to drop fire jars on the enemy decks. But one ship could not defeat a fleet. Soon Muslim marines swarmed onto the flagship, cutting down the men around Theophilus, and taking the strategos captive.

The Byzantine fleet stood by and watched as the flagship fell. Then, slowly, the Muslim fleet turned and sailed away. Almost everyone had benefited from the encounter. The Byzantine fleet had accomplished what they came to do: they had shown that they could respond quickly to any threat to Cyprus. The Muslim fleet had not won a victory, but they had gained something almost as valuable: a Byzantine strategos who was an expert in naval warfare.

Our sources say that when Theophilus was captured, the Muslim commander began a charm offensive to get him to convert to Islam and serve the Caliph. The Muslims had realized that one way to rapidly expand their military and naval capacity was to recruit Christians. Over the centuries, Christian apostates like Ghulam Zurafa (Leo of Tripoli), and Ghulam Yazman (Damian of Tarsus) would be among the Islamic world’s most ferocious and effective admirals. Now, Theophilus was told he could have it all. Wives, money, a position like the one he had before. Actually his position would be improved, since now he would be on what looked like the winning side. Christianity was tearing itself apart over the question of icons. Islam was thriving. Why not join it? Theophilus had been betrayed by his officers. Did he want vengeance? Once he was leading the Caliph’s fleets, he could hunt down the men who had betrayed him.

Theophilus was not willing to convert to Islam. And so the offers went on. One source tells us that Theophilus was kept as a captive for four years. Eventually, the offers began to be combined with threats and punishments. Theophilus was put in prison. He was tortured. Still, at any moment, if he chose to convert to Islam, he could walk free, and step back into a life even better than the one that had been stolen from him.

At first, Theophilus probably hoped that a messenger would arrive from Constantinople, offering a ransom for his freedom. There was, so far as we know, no ransom attempt. If there were any consequences for the commanders who had betrayed him, we do not hear about them. The Empress Irene had her own intrigues, as she fought to keep her son from replacing her. She was probably happy enough with the fact that the Muslim fleet had sailed away after the encounter. And so, as Theophilus sat in prison, he realized that he was alone. Once, he had been one of the most powerful men in the empire. Then his men had abandoned him. His people had abandoned him. His powerful family had abandoned him. Now he lived a life of torment.

Theophilus had been given the world. Then he had lost it. Now he could have it all again, if he wanted it. But it would cost him his soul. And over the years, it became apparent that the man who had once been a strategos would not break. Finally, the Muslims grew weary of their prisoner, and sent him for execution. Theophilus went to die, where in the words of Theophanes, he “was revealed as a noble martyr.”

The world went on. The Byzantines held off the Muslims - barely. Lords and kings rose and fell. The Empress Irene was so determined to cling to power that she had her own son blinded before he could take the throne. In the end, it didn’t help her much, and soon she had fallen and a new emperor sat in her place. It would have been easy to think that in these dark times, power and the struggle to get it was all that really mattered. And yet, for those tempted by despair, there were witnesses like Saint Theophilus, who had faced battle, abandonment, torture, and finally death with the same courage, his eyes fixed on a kingdom that would not pass away.

If you enjoy the Manly Saints Project, please consider signing up for a subscription on Substack, or click here or on the logo below to buy me a beer.