Join me today to meet a saint whose life plan failed spectacularly.

Name: Bogdan Ivan Mandic, Father Leopold Mandic

Life: 1866 - 1942

Status: Saint

Feast: July 30

You can listen to this as a podcast on Apple Podcasts, Pocket Casts, Spotify or right here on Substack. If you prefer video, you can also follow on YouTube and Odysee (unfortunately, videos on Odysee may be slower to update).

At a Church in Padua, a little West of Venice in the North of Italy there was a group waiting for confession. That was not unusual in itself, because so many of the inhabitants of the city, the rich and the poor, educated and uneducated, clergy and laymen liked to confess to one priest in particular. On that day, though, one man hung back. He had come this far, but he still wasn’t sure he could go through with his confession. The man was hesitating, standing at the back of the room and thinking about leaving when someone came out and the little priest popped out of the confessional after him. The priest pointed at the man trying to blend into the crowd, and said that if he was not mistaken, that man was next.

As the two were walking to the confessional, the man tried to prepare the priest for what he was going to hear, saying that he was hesitant because he was a very bad man.

“Not any more,” the priest replied.

The little priest, whose name was Father Leopold, heard confessions full time, often 13 or 15 hours per day. War and fortune and geopolitics had conspired to make his life turn out this way. It was not at all how he had planned things.

And it had been such a good life plan, too.

Young Bogdan Ivan Mandic had formed his life plan many years earlier. He was the fifteenth child of a Catholic couple in the Austro-Hungarian Empire, born in Herceg Novi, in the West of Montenegro, although at the time the city was in Croatia. And that fact, the fact that Bogdan had been born in Croatia, would become the basis of his big plan.

Actually, parts of the plan had been worked out earlier. It had really started in the 1880s with Bishop Josip Juraj Strossmayer. He had realized that perhaps Croatia could be a join between East and West. The Austro-Hungarian empire contained both Eastern and Western Christians. And although Croatia was largely Catholic, perhaps it was far enough to the East to serve as a place where the Eastern and Western churches could begin to be reconciled.

Young Bogdan learned of Bishop Strossmayer’s big idea as he himself was beginning to feel a religious vocation. Along with that vocation, came a persistent sense that God was calling him to work for the reunification of the Eastern and Western churches, the Orthodox and the Catholic. As Bogdan tried to understand what God wanted him to do, it seemed obvious that God was calling him, someone who had grown up in Croatia, for good reason. Bogdan’s life would be about working in Croatia and reaching East. So that was the plan. Enter the Church and then let God guide him to help reconcile East and West.

For Bogdan, this grand project of working to reunite churches was his chance at greatness. Although he was very intelligent, life had dealt him a bad hand. Bogdan was physically small, and would grow to only about four and a half feet tall. He stammered when he spoke. He had stomach problems for most of his life, and he would soon develop arthritis. Perhaps because of this, he tended to be quiet and introverted. Many people with such limitations would not aim so high. Bogdan was hoping to help to do something Christians had been trying to accomplish for almost a thousand years.

And so Bogdan travelled West, to Italy, and entered the Capuchin order in 1884. Bogdan Ivan Mandic became Brother Leopold Mandic. While he was in training, he prepared for his big mission, studying the Slavic languages, as well as working on his Greek. In 1890, he became a priest. By now, Father Leopold was in his late 20s. The thing now was to get back to Croatia.

But things in the Capuchin order moved slowly. By 1897, Father Leopold finally got his chance to travel back to Zadar in West central Croatia. He began to plan for how he was going to work for reunification - only to be reassigned by the Capuchin order and brought back to Italy. They had other plans for Father Leopold. It was difficult to leave Croatia, but Father Leopold accepted that he was a man under authority, so he came back to Italy. He still had time.

The Capuchins were trying to figure out where they wanted Father Leopold. Somehow the only thing that wasn’t on the table was his mission to the East. Despite his requests, in 1909, he was assigned a teaching role at a university - still in Italy. That lasted until 1914, when the Capuchins moved him again. War had broken out in Europe. Italy was on one side, and the Austro-Hungarian Empire was on the other.

Father Leopold was a citizen of the Austro-Hungarian empire. In fact, being an Austro-Hungarian was an important part of his plan. Croatia was part of a big, multinational empire: the perfect place for his mission to the East. But being a citizen of an enemy power left Father Leopold under suspicion in Italy. In 1917, a German and Austrian army crushed the Italians at the Battle of Caporetto. The Italian authorities reacted in part by relocating Austrians living in Italy, and Father Leopold was sent far from the front lines to the South for the remainder of the war.

By now Father Leopold was entering middle age. But there was still time. Then, the First World War came to an end and brought another disappointment. In the aftermath of the violence, the Austro-Hungarian Empire was broken apart. Suddenly the lands that had been unified were fragmented. Even so, Father Leopold still thought Croatia would be a good location in which to work for the union of East and West. He kept telling his superiors about his plan. And slowly he began to win them over.

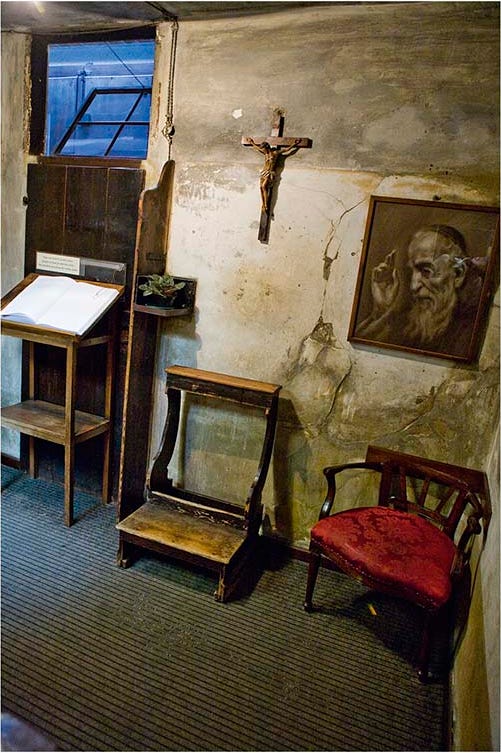

While he was in Padua, the Capuchins had found a task for Father Leopold: hearing confessions. People who confessed to Father Leopold would go away changed, telling their friends about his gentle guidance and spiritual direction. Hearing confessions was not easy - especially for an introvert who was happiest in silence with his books. But Father Leopold threw himself into this temporary assignment, working from morning to night, 13 or even 15 hour days. Soon many in Padua only wanted to confess to Father Leopold.

In the meantime, Father Leopold was preparing for his return to Croatia. Father Leopold was almost sixty years old. He was finally transferred to Zadar where his mission could begin.

But back in Padua, the sudden absence of Father Leopold caused an outcry. When the people of the city learned that the confessor was gone, complaints began to roll in. The parish priest had never seen anything like it, so he escalated it to the bishop. The bishop only held out for a week. After a week, he caved in, and got the Capuchins to recall Father Leopold. And so it was that Father Leopold returned to Padua.

For Father Leopold, this was a crushing defeat. He had worked most of his life to get to his mission to the East. Now he was back in Padua, working as a confessor full time.

But as the years passed, Father Leopold’s perspective on his own life began to change. He still told his friends that he felt like a caged bird. But now, he thought, his ministry in the confessional was his East. It wasn’t just a poetic thought. His life was a sacrifice, an act of humbling himself and restraining his ambition, and his hope was that through this a reconciliation between the East and West might emerge.

One of the things that struck those who went to confess was how humble the priest was. When one man wasn’t sure where to sit, and sat in the priest’s chair, Father Leopold calmly knelt in the spot where the man should have been and heard the confession that way. People who felt they had wandered far from the right path found that Father Leopold always seemed to know the way for to get them back on track.

When someone suggested that Father Leopold was going too easy on the people in the confessional, he scoffed. He was unbinding their sins, just as Jesus had commanded the Church. He added that he wasn’t doing anything really outrageous, like dying for the sins of the whole world.

By now, people from all over the city and the surrounding area came to the small priest in Padua. Intellectuals from the city lined up along with other clergy and working men. Padua became a confession destination.

The years went by, and in his strange, hidden ministry, Father Leopold was growing old. By the early 1940s, Father Leopold was diagnosed with cancer. He began talking about a future that didn’t include him, a future in which his city and church would be devastated by the bombs dropped by the British and the Americans. But not the confessional, he said. God had dispensed too much mercy there for it to be knocked down, said Father Leopold, and indeed, the confessional survived the bombs that began falling in 1943. But in 1942, Father Leopold collapsed as he was preparing for Mass. The Capuchins gathered around him, but he was fading fast. Before evening, he was gone. He was 76 years old. His great plan had never been put into action.

In one way, Father Leopold’s life looks like a failure. Being sickly and with very little physical strength, Father Leopold thought he had been called to do something great, and never managed to even get himself into position to do it. Instead of his great project in the East, he had spent his life in a hidden mission, working in the confessional.

But I think this life has the marks of a manly saint. The longing for greatness makes Father Leopold a manly figure. The humble acceptance that he would not fulfil that great mission is what makes Father Leopold a manly saint.

And there are other ways to look at Saint Leopold’s life. There is the point of view of the people of Padua, who were all but ready to riot at the thought of doing without their beloved confessor. Year in and year out, they saw the priest kindly but firmly breaking people free of the bonds of sin. To them, the suggestion that the frail figure of Father Leopold had not achieved greatness would have seemed absurd.

And there is another point of view, the point of view of the saints. And even if this point of view is not open to us, it may not be a coincidence that twenty years after Saint Leopold’s death, the Eastern and Western churches were closer than they had ever been, as the Catholic Church was reaching East to the “separated brethren” of the Orthodox world.

If you enjoy the Manly Saints Project, please consider signing up for a subscription on Substack, or click here or on the logo below to buy me a beer.