Join me today to meet the saint who tried to sneak into the palace of the sultan.

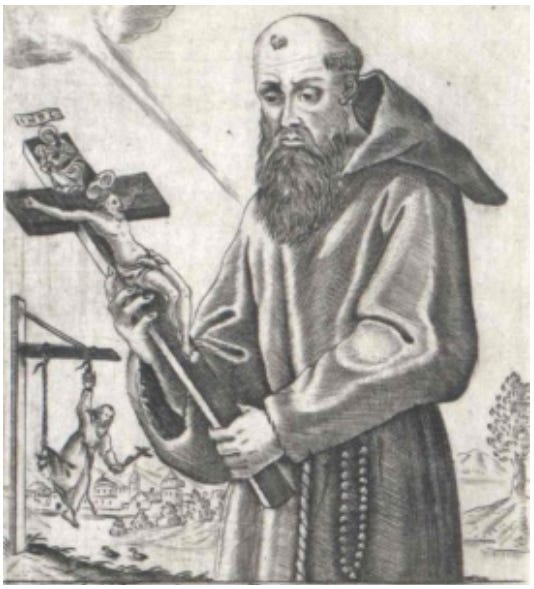

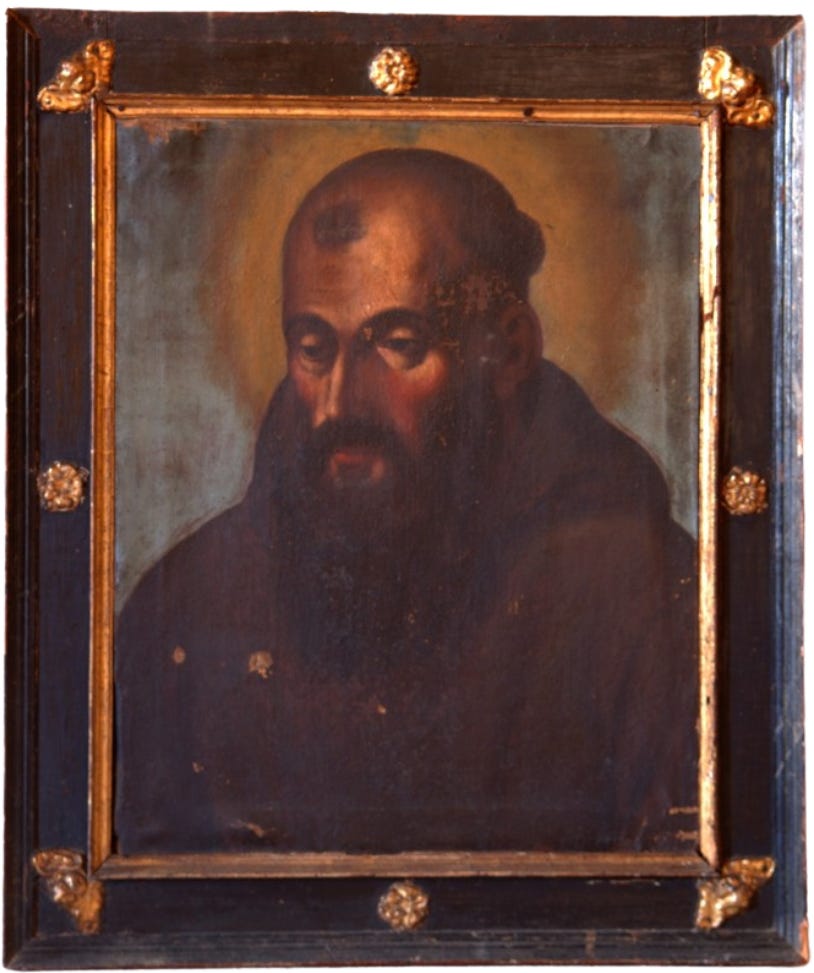

Name: Eufranio Desiderio, Joseph of Leonessa

Life: 1556-1612

Status: Saint

Feast: February 4

You can listen to this as a podcast on Apple Podcasts, Pocket Casts, Spotify or right here on Substack. If you prefer video, you can also follow on YouTube and Odysee (unfortunately, videos on Odysee may be slower to update).

The wandering friar was walking the dangerous paths linking the small villages North of Rome when he realized that he was being followed. He had been told that there were gangs in the area. It looked like one of them had found him. The friar fingered the only weapon he carried and hurried along the road toward an empty country church, slipping quietly in the door. It wasn’t long before he heard the door open again, and the sound of footsteps behind him. There were dozens of them. And there was nowhere else for the friar to go.

Things were working out exactly as the friar had hoped. He drew the crucifix he kept tucked into his rope belt, holding it like the hilt of a sword, and turned to face the gang.

It was almost Lent, after all, and someone had to remind them to come to church.

Few men, few saints even, took risks the way that Joseph of Leonessa did. Sometimes the risks didn’t pay off, and Joseph was laughed at and beaten up - although, even then, those who followed up on the story often found lives changing in the wake of the encounter. And sometimes the risks did pay off. The humble, gentle friar had a way of seeing to the heart of those he had just met. And so it was that, on the first day of Lent, the locals were shocked to see the gang that had until recently been terrorizing their village meekly plunked down at the front of the church.

Joseph was no mysterious wanderer. He had been born nearby, in the town of Leonessa, in the centre of modern Italy, in 1556. Back then he had not been called Joseph. He had been Eufranio Desiderio, a child of a minor noble. Eufranio was born into a world that was no longer medieval but had not quite arrived at early modernity. Constantinople, the last bastion of the Eastern Roman Empire, had fallen more than a hundred years before. The Renaissance had begun. The Protestant Reformation was in full swing, turning the nations of Europe against each other, as Catholics scrambled to find effective ways to answer Protestant critiques. A new world had been discovered, far to the West. In just a few decades, René Descartes, crafter of the scientific method, would be born.

Young Eufranio seemed headed for a comfortable position in this changing world. When his parents died he was taken in by his uncle, a professor. Eufranio’s uncle recognized the young man’s intelligence, and made sure he received an excellent education. By the time Eufranio was in his late teens, the future was looking bright. He had an inheritance, and another noble family had arranged for him to be married to their daughter - an excellent match.

The problem was that Eufranio was quite certain that this was not the future for him.

Eufranio was a teenager when he began feeling a vocation to the religious life. He finally understood what he was being drawn to when he encountered the Capuchins, a new Franciscan religious order. As soon as he was able to do so, he joined the Capuchin Order, and took the name Joseph. By 1580 he was a priest, and soon he was given the task of travelling around Umbria, a region North of Rome, to preach in the towns and villages.

Young Father Joseph preached to anyone who would listen: fellow travellers, aristocrats, peasants, bandits. Some encounters went well, others less so. Good or bad, Joseph went on. The violent encounters didn’t trouble Joseph, and he began to think that perhaps he was being called to be a martyr. Perhaps preaching to bandits had not been dangerous enough. He wanted to go preach in the capital city of the Ottoman Turks, occupied Constantinople.

Western Christians had been worried about their brothers in the East for a long time, and those worries had grown after the fall of Constantinople in 1453. Christians in Muslim lands were under relentless pressure to apostatize and embrace Islam. This was especially true for those Christians who were captured or abducted and sold as slaves, and who could often gain freedom or at least better treatment by giving up their faith. Perhaps no slaves were more miserable than the galley slaves, those forced to row the warships of the sultan. This was why, as the 16th century wore on, groups of monks had sent missions to Pera, modern Beyoğlu, just outside Constantinople, where thousands of Christian galley slaves were kept. A Jesuit mission there had just ended. The Capuchins were considering sending men to take their place.

Father Joseph knew he wanted to be part of this mission. The Capuchins needed three candidates, and Joseph was their fourth choice. Then, at the last minute, someone got sick. Joseph joined the mission, and headed to Venice to sail for Constantinople. On the way, he put his mind to use learning Turkish, and reading everything he could about Islam.

The Capuchin mission found an old, abandoned church, and reconsecrated it to use as their headquarters. A big part of their mission was to the galley slaves, and Joseph went to speak with them often, to bring them the sacraments and comfort them. On several occasions, he offered to take the place of a slave. The authorities said no.

As time passed, Father Joseph began to get noticed in Constantinople. He preached to everyone. Muslims had long used the strategy of recruiting disaffected Christians, and Joseph encountered a man who had been an archbishop in the Orthodox Church, but had lost his faith. He was now a noble in the Ottoman empire, but speaking with Joseph, the former archbishop began looking for a way back. He renounced his conversion, received absolution, and became one of Father Joseph’s companions.

The authorities began to suspect that Joseph would be a source of trouble. They began looking for a mistake on his part, and they found it one night when he came back from the mission so late that he slept on the side of the road. The Capuchins were supposed to spend the nights in the place assigned to them, and now the authorities accused Joseph of spying. He was put in prison for a month, only freed by the intercession of the Venetian ambassador.

When a plague swept through the region, Joseph and the other Capuchins helped everyone they could, growing sick themselves. The other two Capuchins died. Joseph recovered, and worked harder to cover their roles.

The trouble for the Turkish authorities was that Father Joseph had done his research. In 1588, the Capuchins had been granted permission to travel freely through the Ottoman Empire. It was not exactly clear what that involved, but Joseph intended to interpret it in the broadest possible way.

Father Joseph had also developed an apologetic strategy that worked well on Muslims, a kind of Socratic method of question and answer. He preached anywhere he could find an audience, right in front of mosques when that worked well. Lapsed Christians were returning, and Muslims were being quietly converted.

Still, it was not lost on Father Joseph that a confrontation with the Turkish authorities was inevitable. He wanted to get ahead of it, and the more he thought, the more he realized there was only one man who could change the plight of Christians in Constantinople and beyond: Murad III, the sultan himself.

Joseph began to lobby Murad III for an audience. He was hoping to preach to the Sultan as Saint Francis had done centuries before. That might not work, but he also planned to ask for better conditions for Christians. It was a huge risk. But Joseph had risked his life for the gospel many times before.

When Joseph couldn’t get the audience he wanted, he decided to take matters into his own hands. He slipped into the palace. He got by the guards at the gate. Then he passed through the secondary security perimeter, and the third. Father Joseph calmly walked up to the sultan’s bodyguards, who were sitting in front of the doors of the sultan’s personal rooms, and said he was there hoping to speak to their boss.

Joseph hoped that the bodyguards would at least check with the sultan. And perhaps things could have worked out this way. Instead, the bodyguards were embarrassed that this Christian had walked through all their security. They arrested him, and Joseph’s admittedly flimsy argument that free passage for Capuchins meant freedom to sneak into the palace was ignored. Instead, the authorities claimed that Joseph had been trying to assassinate the sultan. Joseph never had a chance to meet with the sultan, even at the trial. He was condemned to death. It would be gruesome: Joseph would have a hook driven through one hand and another through one foot, and he would be hanged over a fire, so that the smoke would dehydrate him as he died.

But Father Joseph was not easily intimidated. As he was hanging, waiting to die, he used his other hand to hold his crucifix. And since no one had thought to gag him, he used the opportunity to preach to anyone who wandered by. Joseph hung like this for a day, then two. He was still holding onto the crucifix, and still trying to preach.

Some readers suggest that Joseph’s plan to sneak in to see the sultan was foolish. But I think they may be missing a few key details. Someone well informed must have told Joseph how to find his way to the sultan’s personal quarters. Did this advisor bet that Joseph would get a sympathetic hearing? If there was any doubt that Joseph’s influence had already come close to the sultan, it was removed when Joseph was sentenced to die, and the network of converts and friends that he had built went into action. Soon, Sultan Murad III was being relentlessly lobbied. His personal doctor asked him to free Joseph. The sultan’s favourite consort and the mother of his heir pleaded for Joseph’s life. The lobbying went on until finally the sultan made a decision. The death sentence would be changed into an expulsion: monks were still welcome but this troublesome Capuchin had to go home.

After three days and nights of being hung over the smoky fire, Joseph was taken down. He was disappointed. He had been hoping for martyrdom. And so Joseph of Leonessa, the almost martyr, returned to Italy. The symbolism of his injuries wasn’t lost on anyone: a half stigmata, one pierced hand and one pierced foot.

Back in Italy, Joseph was offered a chance to be a bishop. He turned it down. He wanted to go back to preaching. Far from being weakened by the experience in Constantinople, Joseph picked up the pace. Those who tried to travel with him found it hard to keep up. He often stopped to preach seven times in a day.

As he travelled on his preaching route, father Joseph did what he could to help the people of Italy. He paused in prisons to speak with the prisoners, especially those condemned to die. Sometimes he would stop to talk to people, apparently at random, advising them against things only he and they knew they had been planning to do. And when there was no one else to help, Father Joseph did the most basic things for the poor, washing their clothes and cutting their hair. In his free time, when he had any, he thought and wrote, writing on logic as well as theology.

Of course, Father Joseph understood that one man’s efforts would only go so far. As he travelled, he kept an eye on the bigger picture. He faced down the aristocrats who were exploiting the poor. He helped to set up hospitals and shelters, planning them, finding the money, and then joining in the construction process.

As he travelled, Father Joseph recognized that the ordinary people were being financially exploited by usury, as bankers grew wealthy thanks to the labour of others. It wasn’t enough to just complain about it, and so Father Joseph set up Catholic alternatives to banks, the strangely-named institutions we remember as Mounts of Charity and Mounts of Grain. The word ‘mount’ is used in the sense of a big pile of something; maybe we would call it a stockpile. Mounts of Charity were piles of money that had been fund-raised so that that the institution could provide loans to borrowers at no interest or at extremely low interest. Mounts of Grain were seed banks, where a farmer could come to receive the seed he needed to sow in Spring, provided only that he gave back the same amount of seed at harvest time.

By the time he was approaching his sixties, Father Joseph was well known and greatly loved by the people of the region. But he was no longer well. He had cancer, a tumour in his groin. For the first time in his life, he was slowing down. He even needed a stick to walk. Father Joseph returned to his hometown of Leonessa. By now the people of the town greeted him as a living saint, and he blessed them. If Father Joseph could see ahead to the rather unseemly way in which, a few decades later, the people of Leonessa would use the occasion of an earthquake to steal his body and bring it home, he did not make any mention of it. Instead, Father Joseph travelled to see the doctor the Capuchin Order had found to operate on him.

The doctor operated on Father Joseph twice - painful operations which we now believe had no chance of success. Even here, Father Joseph seemed to shrug off pain and fear, turning down both anaesthetic substances and the offer of restraints to hold him still, saying that his trusty crucifix would be enough. It was the end of a life lived for others. During the operation, the last words of Saint Joseph of Leonessa were taken from a prayer for the world, written by Saint Fulbert of Chartres five hundred years before:

Sancta Maria succurre miseris.

Holy Mary, help the helpless

If you enjoy the Manly Saints Project, please consider signing up for a subscription on Substack, or click here or on the logo below to buy me a beer.