Join me today to meet a saint who gave up his inheritance to help his people - twice.

Name: John the Harvester, Giovanni Theristes, John Theristus

Life: c. 1049 - 1129 AD

Status: Saint

Feast: February 23, February 24

You can listen to this as a podcast on Apple Podcasts, Pocket Casts, Spotify or right here on Substack. If you prefer video, you can also follow on YouTube and Odysee (unfortunately, videos on Odysee may be slower to update).

The raiders had come from the sea. They had set their eyes on a town named Cursano, near modern Stilo in Calabria, on the tip of the boot of Italy.

In his hall, the lord of Cursano frantically organized the defence of the area. He snapped orders at his men, trying to get them armed, ready and in a fighting frame of mind. He was preparing himself too, shoving on his helmet, strapping on his longsword and perhaps a coat of scale mail, then grabbing a fighting spear and a round shield. His beautiful wife was there in the hall with him, as frightened as everyone else. Then, as he was going out to join his men, the lord of Cursano paused by his wife to tell her a secret: the location of the hidden place in the hall where he kept the hoard of gold and silver that could be used to help the people of Cursano in an emergency. Of course, this was a different kind of emergency, and it would be settled, if it could be, not in gold but with iron.

Everyone knew where the raiders had come from. They had come from the East, from the Islamic Emirate of Sicily, an island so close to Calabria that you could see it on a clear day. Sicily was part of the Islamic world. In the 7th century, Islam had exploded outward, spreading all around the Mediterranean, swallowing up Spain and Portugal in the West and threatening Constantinople in the East. In time, Sicily had been added to those Muslim lands. By then, many towns in Calabria were paying tribute to Muslims from Sicily and Africa, hoping to keep the raiders and slavers away. Sometimes that worked. As the 1040s came to an end, some towns had heard rumours of internal divides in the Emirate of Sicily. The rumours had encouraged them to stop paying protection money. They hoped these divides would leave the Emirate too weak to send out raiders and slavers. Apparently not.

In Cursano, the lord said goodbye to his wife, and went out to face the enemies of his people. But the Muslims had come in strength. Soon, the local defenders were overwhelmed, and the lord of Cursano died, fighting alongside his men. The raiders came to the lord’s hall to loot it. They found the lord’s wife, grabbed her, and dragged her to the ships along with the weeping women of the town. She was a prize, for a beautiful woman like this would fetch a good price in the slave markets of Balharm. And so the woman who had been the lady of Cursano, but was now just another Christian slave, began the miserable journey to the slave market, a journey made even worse by the fact that she was carrying with her a secret.

Even if the people of Cursano had miscalculated concerning the weakness of the Emirate of Sicily, they were at least right to think that change was in the air. After almost four centuries, the Christian West was turning back the East. Yes, Spain was still occupied, but the long battle of Reconquista was well under way. Yes, the Byzantines of the Eastern Roman Empire had fought the armies of Islam at their very gates, but now they were slowly reclaiming territory. And as Christendom held the line, the Islamic world had begun to fracture. Places like the Emirate of Sicily were still dangerous, but now they operated more like independent kingdoms than outposts of an Islamic state.

Europe had also weathered its own barbarian invasions. Europe had been rocked by raids from the Vikings of the Scandinavian North. The Vikings brought violence and war, but soon they were bringing home Christianity. Soon they had begun to change. And perhaps no group of Vikings had changed so much as those led by the warlord Rollo, who took his people to lands given by the king of France in the North of France, around the modern city of Rouen.

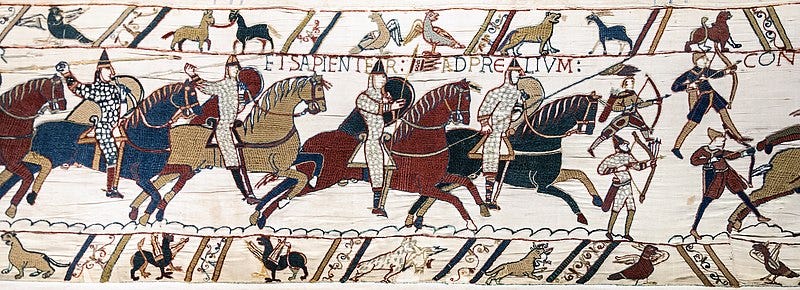

Rollo’s men fought in the old Viking way: on foot, locking their round shields together to form the shield wall and lashing out with sword and axe and spear. These tactics had worked for Vikings from time immemorial, but when they tried them against a force of Frankish knights, Rollo’s men lost badly. Rollo’s heirs would puzzle over this. Soon, they had developed a new way of war, a fusion that took what was best from their past and from the Franks. They imitated the Frankish warriors who armoured themselves in chain mail. They bred powerful warhorses, and learned to ride them into battle. Their shields elongated, so that a rider might protect his legs as well as his chest and head. They began to prefer swords to axes, since a sword was a weapon more easily used by a horseman. And as their power grew, so did the reputation of these Northmen, or Normans, as they came to be known.

The Normans were notoriously tough warriors. One Norman, Tancred, was tough even by Norman standards. He had found himself, so it was said, accidentally caught up in an aristocratic hunt. A lord and his party were pursuing a great boar. They and their hunting dogs had the huge animal surrounded, but it had ripped through their lines and escaped, a few dogs in pursuit. The boar, as it turned out, was luring the dogs away to deal with them on their own. The boar wheeled around on the dogs, by chance stopping near Tancred who happened to be there in the forest. Tancred evaluated the situation and realized what was about to happen to the dogs. The trouble was, Tancred had always liked dogs. And so it was that the nobles rode up to find the boar dead, a sword driven through its skull so hard that only the hilt was visible. Tancred, afraid that he would get in trouble for ruining their hunt, had made himself scarce. The lord tracked Tancred down anyway, but not to punish him. The lord wanted Tancred leading his warriors.

And so the Normans in general, and the family of Tancred in particular, came into their own. Soon, England would be conquered by the Normans. But the sons of Tancred did not go West, to England. They looked South, to Calabria. Earlier, a few Normans happened to be in a city in Calabria when African representatives of the Caliphate arrived in force, demanding tribute and threatening to attack the city. The locals were about to pay when the Normans rode out on their own initiative, easily defeating the Muslim army.

The people of Calabria had not seen warriors like this for a long time. Their king decided to hire the Normans as mercenaries. But people who will not fight their own wars rarely keep their freedom for long, and soon the Normans were acting independently, as warlords, and the sons of Tancred were carving out lands for themselves in Calabria.

The conquest of Calabria by the sons of Tancred was taking place in the fourteen years since the lord of Cursano had fallen defending his home, and his wife had been taken as a slave to Sicily.

The woman who had been the lady of Cursano had indeed gone to the slave markets of Balharm, Palermo as it would come to be known, in the North of Sicily. She was beautiful, and she had been purchased by a local noble who made her one of his wives. In a way, this must have been a relief, for the one-time lady of Cursano was desperately trying to conceal the fact that at the time of her abduction, she was pregnant.

The former lady of Cursano gave birth to a son. The boy was raised as a young Islamic nobleman. When she could, the former lady of Cursano tried to teach her son what she knew about Christianity. Now that her son was entering his teenage years, she realized that he was approaching a time of choosing. It would be very easy for him to become just another lord of Muslim Sicily. And so she told him the whole story. The man he called father was not really his father. The one-time lady of Cursano told her son the story of the terrible raid and the fall of their people. She also told him that it was her faith which made her own life bearable, for Christianity taught that suffering could be a way of drawing closer to Christ. And most importantly, she told him about baptism. She wasn’t sure how it worked, exactly, as she wasn’t one for theology. What the young man gathered was that the people of his father had a special bath, one that could wash away sin.

With this very limited information, the young man faced a choice. He could ignore his mother, follow Islam and embrace the life of a young nobleman in the Emirate of Sicily. Or he could try to find his way back to the land of his father and a world he barely understood. He thought about it. He went to the coast, where Calabria was visible from Sicily, across the Strait of Messina. And then his eyes fell on a boat, which someone had left unatended. He made his decision. The young man ran to the boat, shoved off, and headed for Calabria. One tradition has it that he was pursued, but the pursuers lost track of the little vessel. And so, in time, the boat washed up on the shores of Italy.

Calabria had changed since the young man’s mother had been taken as a slave. The lands that had belonged to his father were now contested by many factions: there were the Byzantines, the Lombards, and of course the Normans led by the sons of Tancred. The people of Calabria saw a young man arrive, dressed in Muslim finery, barely able to speak their language, and they came to the obvious conclusion. He was a spy. He was here representing some other faction, a new Muslim group intending to get into the war and lay even more waste to their country.

The young man was arrested brought in front of a council of the important men of the area. They accused him of being a spy. Of course, there was a language barrier which made it hard for him to defend himself. The locals weren’t sure which was sillier, his attempt to say he was a local himself, or his demand that they give him a bath. The locals came up with an idea sure to break through the language barrier. They would boil the young man in oil, and if that didn’t make him give up his secrets, nothing would.

One of the local leaders brought to see this strange interrogation was the local bishop. As he watched he tried to make sense of the situation. Why was the young man asking for a bath? Just as they were about to dip the young man into the hot oil, something clicked in the mind of the bishop. The bishop waded into the commotion and shouted at everyone to stop. Communicating as best he could, the bishop asked the young man whether he was trying to ask for baptism. The young man enthusiastically agreed. And so the bishop waved away the crowds, and took the young man into his own care. He brought the young man to church and baptized him. Since he barely spoke the language, the bishop gave the young man his own name as a baptismal name: John. And so it was that John, in the house of the bishop, began to acquire the language, the culture, and the religion of Christendom, all at the same time.

Perhaps because he had grown up in a culture which eschewed representation, young John was especially fascinated by icons. He liked to ask people to tell him their stories. On one occasion, he asked about an icon of John the Baptist, his namesake. When he heard the story of John the Baptist, the greatest of the prophets, living in the wilderness and preparing the way for Jesus, John was struck with a powerful sense of vocation. He left the house of the bishop to go into the wild places. And it was there that he came across a small group of monks. They were Basilians, that is, monks living in the tradition established by Saint Basil rather than that of Saint Benedict, who is the spiritual ancestor of most monks in the Catholic Church today. The young man asked to join their community.

The monks said no. Their way of life was austere. John was barely more than a boy. John’s answer was to set up a camp right outside their monastery, trying to live as they did. Every time one of the monks came out, John asked if he could join them yet. Time went on, and the monks couldn’t believe the boy was still there, still asking. Eventually, the monks allowed him to join them, sure that he would soon be discouraged. And when that did not happen, the monks accepted that John had found a vocation among them.

Meanwhile, the sons of Tancred solidified their hold over Calabria. They began to look West, at the island of Sicily. Normans had been in Sicily before - one of their older brothers had been there as a mercenary, and fought and killed the Emir of Sicily in single combat. Now these younger brothers decided to add the island to their holdings.

The Norman force was small, fewer than a thousand knights, massively outnumbered by the soldiers of the Emirate. But the sons of Tancred were confident in their abilities, and few armies had figured out how to handle the fury of a Norman knight. The way one Norman chronicler saw it, being outnumbered was almost an advantage: when a Norman knight lost a horse, there were ten enemies coming at him, ready to die and pass their horses on to him. One by one, the cities of Sicily fell to the Normans. Roger, Tancred’s youngest son, fought, paused to marry his childhood sweetheart who had travelled there from Normandy, fought on, nearly lost his wife to a raid, saved her, and in time claimed Sicily for himself. By 1091, the Emirate of Sicily surrendered. Sicily was Christian again.

John was an established monk by the time Sicily fell. Still, even living among monks, he must have heard that Sicily had been regained. Did John see his mother again? Our records do not say. But we might guess that John had received news that his mother had died, because he took an action that suggests he saw himself as his parents’ sole heir. John went to his father’s ruined hall in Cursano, a place he knew only from his mother’s descriptions. He looked in the hiding spot his mother had told him about, and there was the treasure.

John was rich - if he wanted to be. When John had been a teenager, he had given up his inheritance as a young noble of Sicily, choosing baptism instead. John had gotten his baptism. Now he was an adult, with a second chance to become a great man in the eyes of the world. But John had made his decision. He took the treasure from its hiding place, and distributed it to the poor. War had strained everything in the region, and the people of Calabria needed all that could be done for them.

These were lean times, but all the stories that have come down to us about John are stories of abundance. We have a story of John feeding the hungry, giving and giving even though this small supplies could not possibly have contained all the food he gave away. In John’s world, one bad harvest could mean starvation. Farmers would harvest their grain and let it dry on the ground, and every farmer’s fear was that he might make the wrong guess about the weather, and a rainstorm would blow in while the grain was on the ground, ruining his whole crop. John was passing by one field just as this nightmare scenario played itself out. The gatherers scattered as a storm blew in, and the last thing they saw was the monk John walking the path beside the field. After the storm, to their shock, the workers found the harvest gathered, tied into bundles and neatly placed out of the rain, a task that it would have taken many men days of work to accomplish. The only explanation they could find were the prayers of the monk. They began calling him John the Harvester.

As the 12th century approached, John the Harvester was entering middle age. He was living through the divide between the East and West, between the Orthodox and the Catholic Church. In John’s time, there was still hope of a speedy resolution, and the West was conceiving of a grand gesture of reconciliation, the restoration of the Holy Land to its rightful ruler, the Byzantine Roman Emperor in Constantinople. Suspicion and miscommunication would sour this gesture, and the land would go instead to the lords of the West, the sons and grandsons of Tancred among them.

John would not enter into these controversies, and in time he would be recognized as a saint in both the East and the West. John was near his eighties when his reputation reached the sons of Tancred, now rulers of Sicily and Calabria. It was a grandson of Tancred who first came looking for John the Harvester.

Roger, son of Roger, grandson of Tancred, seemed to have a great future before him. And indeed, his strange, violent path would lead him to bring prosperity back to the region when he became one of the greatest kings of Europe, ruling Sicily and Calabria and extending his domain South to the African coast. He would be one of the champions of the memory of Saint John, called the Harvester. But now any such future seemed in jeopardy. He had taken a slash to his face, and the cut had turned into an ulcer. The wound was painful and disfiguring, and few would want to follow a maimed lord. Unsure what else to do, Prince Roger took a few companions and began to look for the holy man who, it was said, lived in his lands.

When Prince Roger finally found John, it was too late. John had died. The locals were preparing his body for burial. They were more certain than ever that the quiet man who had given up two inheritances to stay among them had been a saint. Prince Roger, sorry to have arrived too late, knelt by the body. Perhaps hoping that people would stop looking at his ulcer, the prince gathered up a fold of John’s cloak and pulled it over his face as he prayed. But Saint John the Harvester had worked greater miracles than this even before his death. And so it was that when Prince Roger stood up from his prayers, to the amazement of his companions, the ulcer was gone.

If you enjoy the Manly Saints Project, please consider signing up for a subscription on Substack, or click here or on the logo below to buy me a beer.

I notice a popular men's worker and new (I think) Christian on Twitter, "X," who lamented the lopsided view of the church's view of men and women but I imagine doesn't know of the Church's amazing legacy of men's courage. I pointed him to your Substack.

Connecting men's fallen state to a loss of higher service to God is needed in our time.