Join me today to meet a highlander saint whose trial shook Scotland.

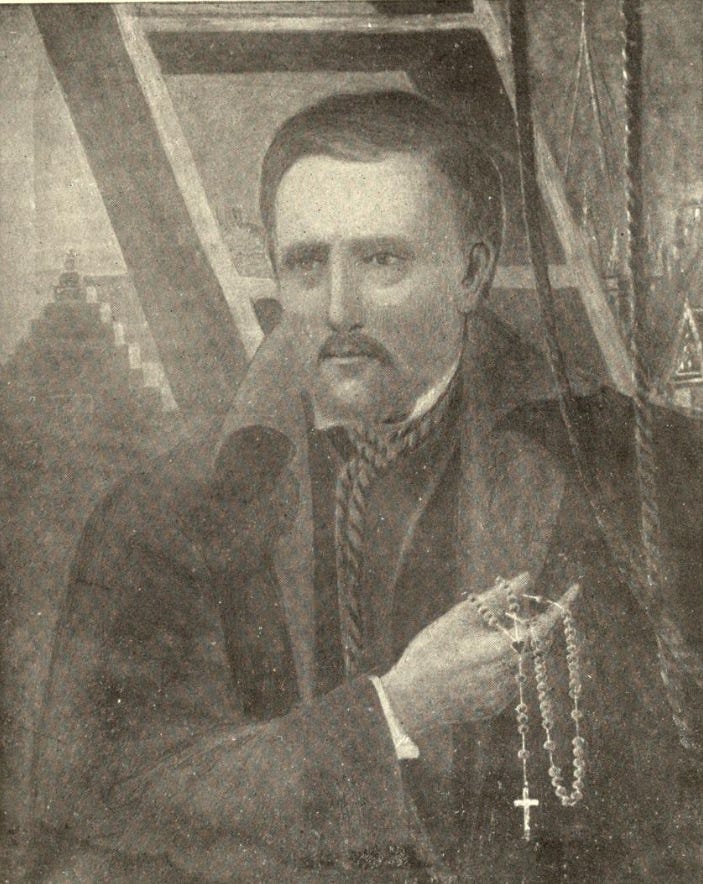

Name: John Ogilvie, alias Captain John Watson

Life: c. 1579-1615

Status: Saint

Feast: March 10 (in Scotland), and October 14 (Outside of Scotland)

You can listen to this as a podcast on Apple Podcasts, Pocket Casts, Spotify or right here on Substack. If you prefer video, you can also follow on YouTube and Odysee (unfortunately, videos on Odysee may be slower to update).

In 1614, one of the spies of John Spottiswood, Archbishop of Glasgow in the new Episcopal Scottish Church, noticed something out of the ordinary. In the city of Glasgow, in central Scotland, the spy noticed unusual activity in a shop. He kept watch. Soon he was sure that something was going on. This was a node in Scotland’s underground Catholic Church. And not just any node. As the spy investigated, he realized that this node even had a secret priest, a man who went by Captain John Watson, but who was really Father John Ogilvie, the son of a highland lord who had become a Jesuit.

When the spy reported to the Episcopal archbishop, John Spottiswood was pleased. He knew exactly what to do with this information. The Catholic Church in Scotland was now all but illegal and existed underground. Paradoxically, the suppression of his Catholic enemies made Spottiswood’s life harder. He was always being attacked by Scottish Reformers who complained that his Episcopal church was too Catholic. Well, thought Spottiswood, he would soon remind them that he was as much an enemy of the Catholics as they were, and make his own name as a loyal servant of the king in the process.

Spottiswood didn’t need to be very imaginative in working out his plan. The English had a template for dealing with Catholics. English courts tended to charge Catholics, not with being Catholics, but with treason, on the grounds that acknowledging the pope meant disloyalty to the English king. In a way, it was a charge that could be raised against any Christian, indeed any man of principle, and Christians had been answering it since the time of Saint Justin Martyr. Even so, trials for treason had proved a very effective way of dealing with Catholics in England. Archbishop Spottiswood was an experienced political player, and now as he sent his men to raid the Catholic gathering, he began to plan how he was going to use the legal system against this Jesuit. How hard could it be?

Spottiswood’s scheme would have been inconceivable even half a century earlier, but over the last few decades, Scotland had been transformed. The seeds of that transformation had been planted long before, for they were seeds of neglect. Like all of Europe, Scotland had been Catholic for centuries, and for a long time the Church in Scotland had been complacent. Many priests were apathetic. Church attendance was low. Children did not learn to defend the faith.

In other countries, a powerful king might rule with the Church in a coalition of throne and altar. Scotland had had a long run of child kings who were represented by regents drawn from the nobility. With a weak monarchy, the lords of the land jostled for position and co-opted Church offices for their children. Soon the Scottish bishops were little more than lords jostling for power along with everyone else.

Corruption in the Church had given rise to a movement of Scottish Reform. The Reformers in Scotland took inspiration from the Puritan reformers of England. Back when Mary, Queen of Scots, was just a little girl, the Scottish regent of the time tried to bring the Reformers into a political coalition. By the time the regent realized how powerful the Reformers had become, it was too late.

And so it was that the Catholic Mary, Queen of Scots, became queen in her own right in 1560 and found herself ruling a country that was being changed. Like the English Puritans, Scotland’s Reformers had reacted to the corruption of the Church by rejecting vast swathes of tradition, tossing out doctrines from papal authority to church hierarchy to purgatory to transubstantiation to confession to apostolic succession. The veneration of Mary and the Saints was idolatry. Crucifixes and rosaries and robes were idolatry. Marking Christmas and Easter was idolatry. The Reformers embraced John Calvin’s doctrine of predestination and suspected that a man who did not read the Bible at breakfast was not among the elect. The Reformers were not led by priests but by ministers, who read the Bible and did as they felt the Spirit of God moved them to do.

At this time there were still many Catholic lords in Scotland. Queen Mary planned to convene Parliament with their help. But the Reformers, led by men like the fiery preacher John Knox, moved faster. A few weeks before Mary was planning to convene Parliament, the Reformers convened a legally dubious session of Parliament in which few Catholics were present. This session of Parliament established the Reformers as the new Scottish church and put out the 1560 Scottish Confession, which explained that the new church would remain united since anyone who carefully read the Bible - well, anyone but a Catholic or an Anabaptist - must necessarily come to the same conclusions.

We can get an insight into the state of the country a few years later when a papal ambassador, or nuncio, came to figure out what was going on. The nuncio found Queen Mary barely hanging onto power. She was almost the last Catholic who dared to admit to being one in public, and John Knox was a powerful figure in Edinburgh.

Knox was none too happy about the arrival of a papal nuncio and, as the ambassador noted, “raged against the Pope as antichrist, and stigmatized me as a Nuncio of Baal and Beelzebub, and an agent of the devil” (William Forbes-Leith, S.J. translation). Ironically, the only time it was safe for the nuncio to meet Queen Mary was during one of John Knox’s hours long sermons, for all her courtiers had gone to hear him. Mary sadly told the nuncio that she could do little for him. She couldn’t even protect him. Putting the papal ambassador under her royal protection would get him murdered for certain.

And so the nuncio disguised himself and travelled through the country. He was shocked and saddened by what he found. He felt sorry for Queen Mary, “scarcely twenty years old and destitute of all human support and counsel”. He had no trouble seeing why the feckless Catholic bishops, most of whom were too timid to even meet with him, had been so ineffective.

The bishops therefore keep quietly at home, and in truth are for the most part destitute of all personal qualifications requisite for taking any lead in such stormy times.

But what most struck the nuncio, as he travelled around Scotland in disguise, was realizing that the puritanical Reformers were not very popular. There was still, he found, a silent majority who preferred the old ways. There was still time, the nuncio reported to Rome, if only this majority had someone to lead them. Queen Mary needed to be provided with serious courtiers - and real priests and bishops, who could model a Church worth defending in their own lives. Mary needed to marry a Catholic prince. The mighty Spanish needed to be told to step in as allies to guarantee Scottish stability as the Church again found its footing. It all needed to happen fast, before the silent majority dwindled and only a faithful few were left.

The nuncio’s advice was not followed, at least not in time. The persecution would intensify. The last Catholic bishop of Scotland was hanged in 1571. Ordinary people who did not attend the Reformed churches faced the prospect of losing their livelihoods and having their children taken from them as religiously unfit parents. Soon Catholicism only existed underground, a loose network held together by a few defiant lords in the Northern highlands.

This was the state of Scotland when, around 1579, a son was born to the highland lord William Ogilvie of Drumnakeith, in modern Banffshire in the Northeast of Scotland, on the South shore of the Moray Firth. William Ogilvie named his son John.

William Ogilvie had converted to the Reformed church. But up in the highlands, customs changed more slowly than they did elsewhere. The Ogilvies were worried about more pressing things, like the doings of their clan enemies, the dastardly Gordons. Highlanders still celebrated Christmas and Easter, and still paid their respects at the holy wells and wayside shrines they found along their paths. Jesuit missionaries slipped quietly through the highlands, finding support or at least toleration among the Northerners.

By the time young John Ogilvie was sent to school in Glasgow, in central Scotland, the Reformed ministers were at the height of their power. Queen Mary had been forced out of Scotland, and her son James VI ruled in her place. James was a Protestant, but not one of the Reformed variety. The Reformed ministers heard shocking rumours that his court tolerated sins like dancing, and the last straw was when they learned that James was not reading his Bible at breakfast. A delegation of ministers came to inspect the court, and the frightened king let them follow him around and reorganize his life. Only James’ wife, Queen Anne, had the courage to tell the wives of the ministers, who were supposed to be following her around, that she would be unable to fit them into her busy schedule of dancing.

By the time John Ogilvie was entering his early teens, he had a chance to travel to Europe with another noble young man to receive a continental education. At this point, there is a little bit of a mystery about John’s studies. The Catholic Church had, belatedly, taken the advice of the nuncio who recommended setting up a Scottish College. By now it was too dangerous to set it up in Scotland, so it was set up in Douai, in the North of modern France. Somehow, John ended up attending this college.

Why was a young Protestant noble at a Catholic college? Possibly there was some sort of miscommunication with his parents. Or perhaps the Ogilvies were still more attached to the old Church than they let on. Our early sources suggest that John himself sought out the college. He had been in an argument with a Catholic, and found there was an enormous difference between someone properly catechized and the sorts of people he knew back home. John wanted to hear more.

It’s hard to believe that such a young boy would have these sorts of intellectual convictions. Then again, John Ogilvie was growing up to be an intelligent young man. In time, he would gain a reputation for his intellect and rapier wit. Whatever brought him to the college, soon Ogilvie was feeling a religious vocation. He began a course of study to become a Jesuit.

Ogilvie’s studies would take him across Europe. He studied in Brno, in the Southeast of the modern Czech Republic, for ten years. Then he studied philosophy in Graz in Southern Austria, becoming a professor himself. He was moved to Paris and was ordained a priest. But John sensed that his destiny lay in his homeland of Scotland. In 1613, John Ogilvie was in his early thirties, and the Scottish mission was ready for him at last.

By now it had gotten still more difficult to be a Catholic in Scotland. Even people trying to leave the country were forced to swear not to go Catholic once they left. But now, the power and influence of the Reformers was being checked. A new player had entered the game.

In England, Queen Elizabeth I had died without an heir. The crown passed to King James VI of Scotland, who thus became King James I of England as well. James had always been a Protestant, but he disliked the Reformers. Now he had another option. As King of England, James had inherited the role of head of the Church of England. The Episcopal Bishops who were known as Anglicans in England began to make their power felt in Scotland, now with royal support. Only a few years earlier, men like John Spottiswood had been in trouble with the Reformers, accused of enjoying a game of cards in Church. Now Spottiswood, Episcopal Archbishop of Glasgow, had begun his rise to power.

The Archbishop of Glasgow was in control by 1613, when three disguised Jesuits arrived at the port of Leith, now within the city of Edinburgh in Eastcentral Scotland. Father Ogilvie took on the alias of Captain John Watson, retired soldier, and rode North, toward the highlands.

We know that Ogilvie visited his family, though we do not know what they thought of the life he had chosen. He visited some of the lords of Scotland who were still Catholic. He moved around the country, following the secret Jesuit maps that catalogued the remaining Catholic communities and showed the locations of caches of the things a priest might need for the sacraments. After a time, Father Ogilvie went South into England. For some reason, in 1614, he took advantage of the fact that it was easier to leave from England and returned to Paris. Whatever his motivations, he did not stay long, and soon he was back in England, heading North into Scotland, to the city of Glasgow.

In Glasgow, Father Ogilvie began to gather the Catholic network. One influential local Catholic sold horses. Ogilvie’s alias of Captain John Watson became a horse expert, travelling through the region and visiting all the stables - ideal places to celebrate a private Mass. Catholics who wanted guidance or confession could travel with Father Ogilvie as he wandered the land looking for horses. Many Catholics had all but lost hope, but began to find it again thanks to the charismatic young priest.

That was when Archbishop Spottiswood’s spy noticed something unusual going on in a Glasgow shop.

The spy had been lucky. The shop he had noticed was the main intake for the Catholic network in Glasgow. It seems that the shopkeeper was careless in screening newcomers. Soon, the spy had mapped out the entire network.

And so it was that, in 1614, Archbishop Spottiswood’s men burst in on a Catholic gathering and arrested Father John Ogilvie and many of his flock. And then, almost immediately, things started going wrong for the Archbishop.

The plan was to threaten everyone with torture and secure their cooperation. That worked well enough on the laymen. But on the very first night, Father Ogilvie was threatened with a torture where his legs would be squeezed until the bones broke. The idea was that he would be so intimidated that he would cooperate. He told his captors to go ahead and do it. They had not been expecting to have their bluff called, so they began to backpedal, and a dynamic emerged that would last through the trial.

In England, lawyers had figured out how to get Catholics to self-incriminate. That turned out to be trickier than the Archbishop anticipated. Father Ogilvie had spent the last twenty years learning philosophy and disputing at the best universities of the continent. The prosecution kept trying to close the logical trap around Ogilvie, only to find that he had escaped with some clever distinction. Soon the prosecution was accusing Ogilvie of somehow cheating and twisting their words, and insisting that they would write out the charges and just read them so that he couldn’t fumble them with some clever retort.

The trial became a disorganized mess. Soon it was about everything. At one point discussion veered into the question of a priest who had died in England to preserve the seal of the confessional. Spottiswood huffed piously “If any one should confess to me anything against the life of the King I would betray even a person who confessed.”

To which Ogilvie replied, “No one had better confess to you.” (Karslake translation)

At one point the prosecution became so desperate that they argued that Ogilvie was actually an impostor, a local troublemaker just pretending to be a Catholic priest. They brought in the troublemaker’s mother as a witness, but she blew up the scheme when she mentioned that her son could always be identified by his deformed hand.

The worst part of the trial, at least from Archbishop Spottiswood’s point of view, was that Ogilvie turned out to be so very likeable. Early on, when Ogilvie was fresh from his arrest and when the archbishop still controlled the narrative, another highlander met Ogilvie and angrily said he ought to throw this traitor into the fire. Ogilvie was fresh from a beating and he was coming down with a fever, so he replied “[i]f you should decide to put me into the fire it could never happen more conveniently than now, as I am very cold”. The other highlander spluttered, but soon people were chuckling at the witty priest, and even the other highlander began to grin. Ogilvie had a way of turning his enemies into friends, and the longer the trial went on, the more friends he had.

Eventually, Ogilvie was moved from Glasgow to Edinburgh, where, it was hoped, things could be done right. The prosecution arranged for an angry crowd to meet him on the way, screaming and throwing things at the prisoner. Father Ogilvie was not shaken. He wrote:

A certain woman cursed “my ugly face.” To whom I replied, “the blessing of Christ on your bonnie countenance,” thereupon she openly protested she was sorry for what she had said, and would never more after that say anything bad about me.

The trial did not get any less bizarre. There was never any doubt that Ogilvie would be found guilty of something - the gallows where he was to be hanged were already constructed before the trial had come to an end. But the longer the trial went on, the more sympathizers Ogilvie had, both inside and outside the courtroom. Archbishop Spottiswood was heard moaning that he would give a lot of money for a do-over, one in which he just left Ogilvie alone.

In Edinburgh, Ogilvie was tortured though sleep deprivation. Any time he nodded off, he would be forced to wake up, until he had not slept in more than a week. But now there was a carrot as well as a stick, for the Episcopal Church had been so impressed that they hoped Ogilvie would join them. They offered him an excellent academic position that came with money and a wife. Ogilvie dryly told them that the sleep deprivation for more than a week left him unable to think, and if they wanted someone who was practically braindead for an academic role, that didn’t say much about how they were running their colleges.

By the time of sentencing, Father Ogilvie had so many admirers even in the court that Archbishop Spottiswood tentatively floated the idea of exiling Ogilvie instead of executing him. What would happen, the Archbishop asked carefully, if they just kicked Ogilvie out of the country? Ogilvie told them that Scotland was his home. These were his people. He would come back as many times as necessary, and he would work on everyone, including Spottiswood himself. The court was backed into a corner. They condemned Father John Ogilvie to die by hanging. Ogilvie thanked the court, blessed them, and shook the Archbishop’s hand.

Now that the trial was finally over, Archbishop Spottiswood hoped to have the last word. But as it turned out, Father Ogilvie had been taking notes, and the sad, funny story of the circus that had been his trial would be smuggled out of Scotland to be read and mocked throughout Europe.

It was left to Father Ogilvie’s little flock in Glasgow to finish the story. By the time of the execution, the unbreakable priest had many secret Catholics watching in the audience. They heard someone ask Father Ogilvie whether he was afraid, and Ogilvie reply that he didn’t fear his martyrdom anymore than the man asking him the question feared his dinner. The crowd heard a Calvinist minister warn Ogilvie that this was his last chance to turn to the Reformed church, and Ogilvie teasingly reply that the Calvinist had picked a fine time to start believing that people had free will.

It was left to the people watching in the audience to tell a story of courage and defiance to the end. If the point had been to demoralize Catholics, the trial had the opposite effect, for public records show Catholics emboldened and encouraged. It would be a century until Catholicism could be practiced freely in Scotland again. But Saint John Ogilvie had shown the faithful remnant what they were fighting to keep, and now, they would find the courage to hang on.

If you enjoy the Manly Saints Project, please consider signing up for a subscription on Substack, or click here or on the logo below to buy me a beer.