Join me today to meet a saint whose Christmas gift-giving ended with a surprise.

Name: John Cantius, Jan Kanty, John Kęty

Life: 1390 - 1473

Status: Saint

Feast: December 23

You can listen to this as a podcast on Apple Podcasts, Pocket Casts, Spotify or right here on Substack.

It was late, very late on Christmas day in Krakow.

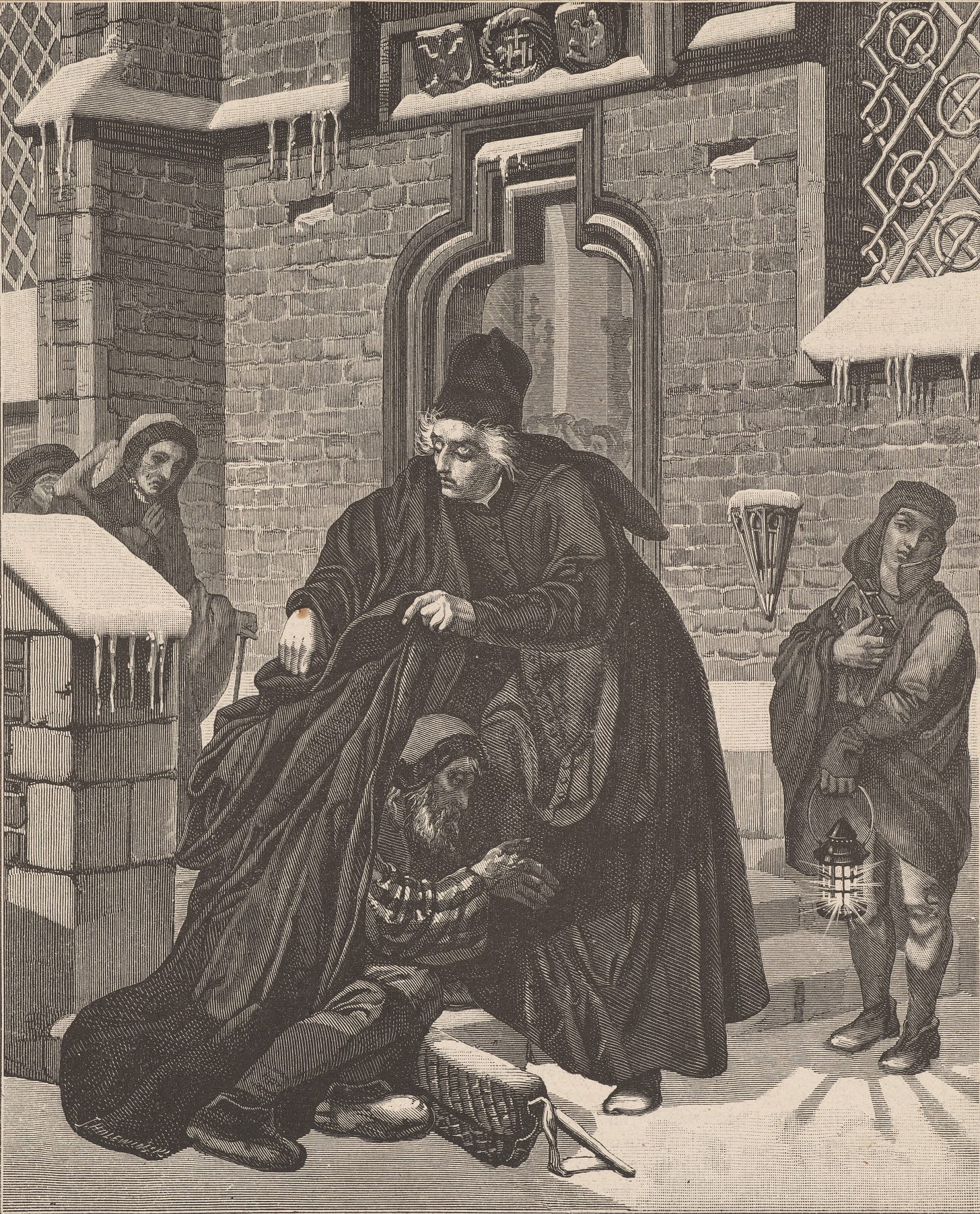

The sun had set before it was even 4 o’clock. That was hours ago now. The cold wind whipped through the city and there was snow on the ground. Those going to church for matins at midnight hurried along to get through the cold. But the priest and professor John Cantius stopped when he saw a beggar in the street. The man was huddled up against the cold, and without even thinking about it, the old professor gave the man on the street a Christmas gift. John took off his warm cloak and wrapped it around the man’s shoulders.

Shivering, John Cantius hurried on to matins.

This sort of charity was not out of character for John Cantius. His colleagues at the university had gotten used to seeing the professor return with his academic gown awkwardly pulled forward to hide his feet. He was trying to avoid attention, but they knew the signs. John had given away his shoes. Again.

Giving away what he had to the poor was one part of John Cantius’ quiet but firm life of witness. He was determined to live an old fashioned Catholic life. Once, that might have been easy. But all around John things were changing, so that standing still became one of the hardest tasks of all.

The middle ages were coming to an end.

Central Europe, where Cantius lived, had until recently been the scene of the Northern Crusades, led by the Order of the Teutonic Knights. But then the Order’s great enemy, the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, had joined forces with Poland and the Grand Duke had become a Catholic. The crusaders were defeated in 1410, and history went on without them as Lithuania continued to Christianize anyway.

The church was in turmoil. There had been decades of scandal as popes battled antipopes. The Western Schism at last came to an end in 1417, but it left the church weakened and discredited in the eyes of many. There were a few figures for the church to rally around, like John of Cantius’ personal hero Saint John of Capistrano. But the challenges for the church were coming hard and fast from would-be reformers like John Wycliffe in England and Jan Hus in what is today the Czech Republic.

Professors had their own problems. The medieval way of doing philosophy was to show how Aristotle and his tradition could be reconciled with Christianity. This project now felt tired and constricting. Thinkers were starting to ask, why Aristotle? Why not some other ancient philosophy, why not the Stoics, or the Epicureans, or the Skeptics? It was a good question, but it was not obvious that all these traditions could be made compatible with the church. It wasn’t even clear that this was desired anymore. Perhaps, some thought, attention should be given to the magic of the Hermetic tradition, as new texts began to circulate in the 1460s.

John Cantius was born into this changing world in Kęty, a small town in the South of Poland. He was an intelligent young man, and he studied philosophy in Krakow. He completed his doctoral work and taught philosophy, then returned to study theology and become a priest. Somewhere along the line, John had decided that he was not going to be swept along with the times. John didn’t mind if people thought of his approach as a little boring: he would settle for not contributing to any of the scandals in the church. John also didn’t mind if people thought of him as old fashioned. He was going to practice philosophy and theology in a way that was Catholic, not just nominally Catholic, but authentically, sincerely, driven by faith.

And so, over the years, John Cantius set himself up as a professor and academic. He worked on the philosophy and physics of motion. He felt the weight of his responsibility for the young students who came to him to learn, and he tried to teach them good things. John lived humbly in a small room at the university, giving away his possessions to the poor whenever he saw an opportunity - as when on Christmas he gave away his cloak.

One of the old fashioned things that John Cantius embraced was the idea of pilgrimage. When he had the time, he would put his belongings on his back and begin the long walk to Rome and, once, to Jerusalem. If possible, he’d time it so that he could hear Saint John of Capistrano or Saint Bernardino of Siena as they passed along his way on one of their preaching tours. Pilgrimages were dangerous. At first everyone advised the professor that he should not go. It would be physically exhausting. There was a very real possibility that he would be robbed, even killed on the way.

Yes, John Cantius told them. That was the point of a pilgrimage.

As it happened, John did get robbed on the way. The robbers surrounded him and took the bag where he kept his money. After they had done so, they asked him if he had any other money, and he said no.

But as the robbers were walking away, John remembered that he did have more money. He had used the old pilgrim’s trick of sewing a few gold coins into the hems of his clothes for exactly this sort of situation.

So John ran after the robbers, shouting at them to wait.

They warily turned around.

John Cantius explained that he wanted to be truthful. He did not think it was right to lie to the robbers. He did, in fact, have more money, it was just that he had forgotten. The coins were in the hems of his clothing.

The robbers had never before had anyone run after them like that. Perhaps it was something in the way John Cantius spoke to them that made them unsettled.

They gave him back what they had stolen, and asked for his blessing instead.

John Cantius was always happy to give that.

When he was back home in Krakow, John was, in time, made the Dean of Philosophy. And now John’s determination not to be swept along by his times was something he could apply to his department as a whole. John made it clear that under his leadership, Krakow would be an authentically Catholic department of philosophy. He also recognized that personnel is policy, so he made sure that the new humanists would not find a home in his department. All around him, in other cities in Europe, scholars were grappling with new ideas. John knew about them, but decided the new ways would not prevail on his watch. Many people liked his approach. Of course, not everyone was of the same mind, and John started to make enemies as well.

One habit that John shared with many of the new humanists, though, was writing on the walls. Alone in his small room, he often wrote quotations, Bible verses or insights on the walls, so that he lived in a little cloud of wisdom. The saying that is usually associated with him is a little Latin rhyme, which goes like this:

Conturbare cave: non est placare suave,

Infamare cave; nam revocare grave.

which translates as:

Beware of troublemaking, it’s not pleasant to make things right,

Beware of slandering, it’s hard to take back what was said.

That’s good advice, to be sure. It sums up John Cantius’ public life: even though he was determined not to change, he was never aggressive or unpleasant about it. He just planted his feet and didn’t move.

But if you wanted to know what John was thinking as he went through life, the key inscription was just two words:

ut supra

The literal translation is ‘as above’. When John Cantius had to do something he was not sure how to do, or that he did not want to do, he liked to say these two words to himself. “As above.” They echo the Lord’s prayer, of course, the idea that things here below on earth should be as they are above in heaven. But the words also undercut the magical method of the Hermetic tradition, often summarized “as above, so below”. The idea is that a magician can employ cosmic rules to impose his will on the world we live in. John Cantius saw things differently. His goal was to adjust his will to God’s order. He was much more interested in the way things were above than the way they were below.

And so when John Cantius’ enemies succeeded in pushing him out as Dean, John said quietly to himself, ut supra. If God wanted him elsewhere, then elsewhere he would go.

Because John Cantius was a priest, he could be moved around by the bishop. His enemies had found a way to have him reassigned to a tiny, rural parish in the village of Olkusz. It was almost a punchline: the professor was going to go deal with peasants who were squabbling over stolen livestock.

John Cantius, though, was determined not to turn his new assignment into a punchline. If anything, it weighed on him more heavily than his academic work. Previously, he had been charged with shaping the young minds of the students. Now he was responsible for all the souls in his parish. He didn’t want to have to explain to God how snootiness on his part had driven someone away from the church. What is more, John was pretty sure that God did not send men into situations that they could not handle. And so John set out to be humble, to work hard, and to become a parish priest.

The people of Olkusz didn’t like the idea of an intellectual priest at first. But as they dealt with John Cantius, they realized he wasn’t going to go off on philosophical tangents or be condescending to them. He wanted to help, and they soon found they didn’t want to do without him. Unfortunately for the parish of Olkusz, the University of Krakow was reaching the same conclusion. By the time John Cantius was commanded to return, the people of Olkusz followed their now wildly popular priest down the road for miles on his trip back.

And so it was that John Cantius was once again Dean of Philosophy. He would have three decades to shape the university department into what he wanted it to be.

Over those decades, John became known outside of the university, in the city of Krakow. People knew the professor was always willing to give what he had, and that this was sometimes more than it appeared to be. One of the most famous tales of the saint has it that he was passing through the market when he saw a servant girl crying. She had accidentally dropped a clay jug. Worse, the jug had been full of milk that she was bringing back to her mistress. The jug was broken, the milk was gone, and she knew that she was in for a vicious beating when she got back home.

John picked up the pieces of the jug, fitting them together in his hands until he handed the jug back to the surprised girl who realized it was whole once more. He told her to and get water from a nearby stream. When she handed him the filled jug, John blessed it, and gave it back to the girl. She looked at it and found it was once again full of milk.

By the time John Cantius was dying, he was an institution. He called his colleagues to his death bed. He told them how important it was to stand firm. And he told them, again, how heavy a burden they all bore, for it was their duty to wisely mold the the young minds in their care. John Cantius is a manly saint, because he had been standing firm in opposition to the times for so long that he made it easy for others to follow his example. John launched a Polish tradition of academic Catholicism - a tradition that remains one of the currents in Polish philosophical scholarship. In fact, for centuries, philosophers at what would become the Jagiellonian University would symbolically put on the cloak of John Cantius on special occasions.

Which brings us back to the story of when John Cantius gave his cloak away on a cold Christmas night. After church, John returned to his room. And when he got there, he discovered a quiet Christmas miracle.

The cloak was hanging there on the wall, just where it always was. And through the Christmas season, and in the years that followed, Professor John Cantius thought again and again of Who it was he had really clothed with his gift on Christmas day.

If you enjoy the Manly Saints Project, please consider signing up for a subscription on Substack, or click here or on the logo below to buy me a beer.

Nice. Our universities could use him now.

Reminds me of St. Martin--Christ has a knack for acquiring cloaks from virtuous men!