Join me today to meet a martyred protector of the unborn.

Name: Hallvard, Alfward, Hallvard Vebjørnsson

Life: c. 1020 - 1043 AD

Status: Saint

Feast: May 15, July 19

You can listen to this as a podcast on Apple Podcasts, Pocket Casts, Spotify or right here on Substack. If you prefer video, you can also follow on YouTube and Odysee (unfortunately, videos on Odysee may be slower to update).

Hallvard met the woman as he was preparing his boat near Drammen, just a little Southwest of Oslo in Norway. He was about to shove out into the Drammen Fjord, probably headed North to Lier. The woman was visibly pregnant. She said she was being pursued by killers. She begged Hallvard to take her with him.

Hallvard helped her aboard and finished his preparations for departure.

Hallvard was a Christian, part of the new generation of Christians in Norway who had grown up in the wake of the reforms of King Olaf II, Saint Olaf as we remember him today. Christians had been in Scandinavia for a long time. But some decades earlier, King Olaf had set about bringing Christianity to absolutely everyone, including to those isolated areas that had heard nothing of the Gospel.

For example Olaf led a small group of men to a valley ruled by a powerful local lord, Guthbrand, whom the poets had honoured with the title of shield-breaker. Guthbrand heard that King Olaf was coming, and decided that he wanted nothing to do with the new religion. He summoned his men and explained the situation.

A man by the name of Olaf has come to Loar intending to force us to adopt a new faith, different from the one we have held till now. He wants us to destroy all our gods, claiming that his god is much greater and stronger. It’s strange that the earth doesn’t open up under his feet when he says such things and that our gods allow him to go on living. But Thor has always supported us, and I’m certain that if we carry him from his place in the temple, here on this farm, then Olaf, his god, and his men will all vanish into nothing, as soon as he looks at them. (A. A. Sommerville translation)

It was indeed strange that the old gods who had protected these lands for centuries were now silent. Guthbrand took matters into his own hands, raised almost a thousand men, gave command to his son and sent them against the king’s small expedition. But experience won out, and Guthbrand’s levies broke and ran when Olaf’s warriors hurled a volley of spears. Afterwards, Guthbrand blamed the whole thing on his son’s inexperience and cowardice. But then, that night, Guthbrand dreamed of a man who appeared in glory and in light, and though he did not know who or what the figure was, Guthbrand was afraid.

“Your son did not have a successful foray against King Olaf,” [the man] said, “and you will fare even worse if you insist on fighting with the king, for you and your entire army will perish; wolves will drag you and your men away and ravens will tear your flesh.”

Guthbrand was terrified by this dreadful vision and spoke about his dream to Thord Paunch-Belly who was a chieftain in the Dales.

“I had the same dream,” said Thord. (A. A. Sommerville translation)

Soon King Olaf and his men were in Guthbrand’s town. The Christians smashed an idol of Thor. Again, nothing happened to them. Christians said that they worshipped the Creator, “a great God, and a great King above all gods” in the words of Psalm 95:3. It was hard to describe the situation any other way, as the old gods of Scandinavia seemed to slip away into the shadows, like rebellious servants upon the Master’s return. Guthbrand and his men embraced the new faith.

And so it went in encounters across Norway. One poet put it this way:

All my lineage shaped lines praising Odin’s reign; I remember precious poems, the work of my ancestors’ age;…Let Freyr and Freyja rage at me - last year I left Njord’s mysteries - let mighty Thor’s fury face me, let the gods find grace in Grimnir [another name for Odin]; with all my love I will call on Christ, the only God and great father; awful for me is the anger of the Son, whose power prevails over the world. (A. A. Sommerville translation)

Hallvard was just a boy when King Olaf II was travelling the land, bringing the Gospel with him. Other kings had ruled after Olaf. There had been King Cnut, who was king of England also. Now the son of Olaf sat on the throne, Magnus, who was called Magnus the Good. Tradition has it that Hallvard was distantly related to the king. But Hallvard was not a war leader. He was a merchant.

Hallvard probably traded in the Baltic and the North Seas. The vast trade networks that had existed in the Roman period were now gone. Such luxuries as Italian wine and African ivory were no longer easy to get. But this had opened new opportunities. Hunters harvested the tusks of walruses. Even grape vines could be found far to the West, in a place that had been named for that discovery: Vinland.

It might seem strange that Hallvard chose a merchant’s life despite his noble heritage. But in these early days of the 11th century, Norway’s social hierarchy remained fairly flat. Yes, society still broke into the threefold structure that had been instituted, so the poets said, by the god Heimdall. There were thralls, karls and jarls, that is, a lower class of slaves, a middle class of free men who farmed or traded or fought and sometimes did all these things, and an upper class of ruling nobles. But even though the hierarchy existed in theory it was flattened by the sparseness of the population and the coldness of the climate. Every man’s labour was important, which meant that every man mattered. Even the king would sit among the common people to judge and speak with them, and it was not a dishonorable thing to live the life of a merchant. And besides, being a merchant was not easy work.

A merchant going from port to port needed to understand the sea and the weather, of course. He would have to watch the winter to guess at the trading season that was to come, roughly beginning in April and ending no later than October. A merchant needed to know the stars because he would use them to navigate on the open water. He also had to understand his ship, keeping a supply of sail cloth, thread, needles and carpentry tools on hand. No one was going to buy from a merchant who limped into port in a dingy boat.

Once he was in port, there were a whole lot of other things a merchant needed to know. He had to understand the dialects of the North, and if he went South he’d be well served by learning the language of the Franks, the Saxons, and Latin as well. Those languages would help him master the details of local laws. It was all too easy for an inexperienced trader to get in trouble by violating some local law, such as by not removing the dragon head on a long ship when sailing into a pagan port and thus potentially scaring off the guardian spirits of the place he was visiting.

A merchant needed to exercise prudence. A prudent merchant didn’t hide the flaws in his merchandise, but didn’t undervalue it either. No matter how well you understood the local laws, prudence also dictated that you should make sure big transactions were witnessed by several reliable men around the market. Plus, a prudent merchant might get wind of a big feast, when nobles would drink and make vows and boasts about what they would do in the next few years, essentially spelling out their upcoming policy agenda.

Perhaps above all, a merchant needed to be able to control himself. Markets offered all sorts of temptations. You could waste your take on drink or food or women. You could blow it all gambling on a stallion fight, where men goaded spirited horses into battling it out with tooth and hoof. You could get hurt in a fight, as sometimes happened when the men shoving their stallions together decided to join in the fight themselves, and the horse battle turned into a general brawl. It would be safer to enjoy the harmless fun of a mock lawsuit, a strange form of entertainment that emerged in the litigious North. This was a fake trial in which men made a silly argument - often complaining about their wives - and rendered a mock judgment to the amusement of the onlookers.

The merchant who could find his way through all these challenges could grow quite wealthy. Even though Hallvard is usually portrayed as a young man in his early twenties, there is some evidence from what happened next that Hallvard had achieved a level of success himself. A successful merchant would find partners, men who could sail their own ships, or locals who could man a permanent market stand in some of the bigger markets. Hallvard, it seems, was heading North over the Drammen Fjord to meet some such friends or partners.

Before Hallvard could get into his boat, though, the pregnant woman ran up and asked to come with him. Hallvard agreed, and she climbed in. But he had barely gotten away from the shore before three men came running along the bank. They demanded that Hallvard hand the woman over to them.

Many readers have speculated that the woman must have belonged to the lowest class in Northern society, the thralls, or slaves. Perhaps she did, although I find that makes the behaviour of the other people in the story more difficult to understand. If the woman had been a runaway slave, that would be reason enough for the men to demand her return. Instead, the men accused the woman of theft. So perhaps she was a free woman who had fallen on hard times - perhaps recently widowed, given the fact that she was pregnant but there was no mention of a husband.

Hallvard suddenly found himself obliged to render judgment on the situation. Was this woman a thief? Or was something else going on? Hallvard was outnumbered three to one. But on the other hand, he was in a boat, and if he rowed hard he could probably escape the men on the shore. And so the standoff turned into a conversation, with Hallvard trying to guess what was really going on.

The men on the shore said that the woman had broken into a house and stolen from within it. She denied this. The men said they were seeking simple justice. And, to judge from the telling of Adam of Bremen, they may have appealed to Hallvard on the ground of kinship as well, whereas the woman may have been from a family unfriendly to his own people. The woman said that the men on shore intended to murder her. She affirmed that she was willing to undergo a trial and face the ordeal of the hot iron. This meant she would be forced to carry a heated iron bar, the idea being that an innocent person would be given grace to do so but a guilty person would be burned. The men insisted they had no intention of harming the woman, but said that there was no need for a trial because her guilt was established beyond a doubt.

Hallvard found himself in the middle of a situation in which it was not obvious who was lying, or what was the right thing to do. This called for wisdom. As he thought through what he had heard, several things struck Hallvard as out of place. The woman was being accused of smashing in a locked door. He doubted that she had the physical strength to do that - especially not while pregnant. It was odd that the men were not willing to let justice take its course and give the woman her trial by ordeal. And there was another person in the situation. There was also the woman’s unborn child. Whether the woman was a thief or not, the child was certainly innocent of these charges.

And so Hallvard made his decision. He would take the woman to safety. The men would have their chance to bring formal charges. Hallvard began to pull the boat out into the Drammen Fjord.

That was when the men on the shore drew their bows.

People sometimes suppose that Viking warfare did not rely on the bow. And while it is true that Viking warriors are usually shown with the axe or sword, this did not imply a lack of skill in archery. Some years earlier, the great heathen brotherhood of the Jomsvikings had been drawn into an ill-advised attack on Norway. Even after their defeat, one of the Jomsvikings who had been left for dead on a ship had balanced himself on the chopped off stumps of his legs, drawn his bow and sniped a richly dressed man on the shore. Unfortunately for him, the man was a merchant with a taste for finery, and not the enemy Jarl he had hoped to kill.

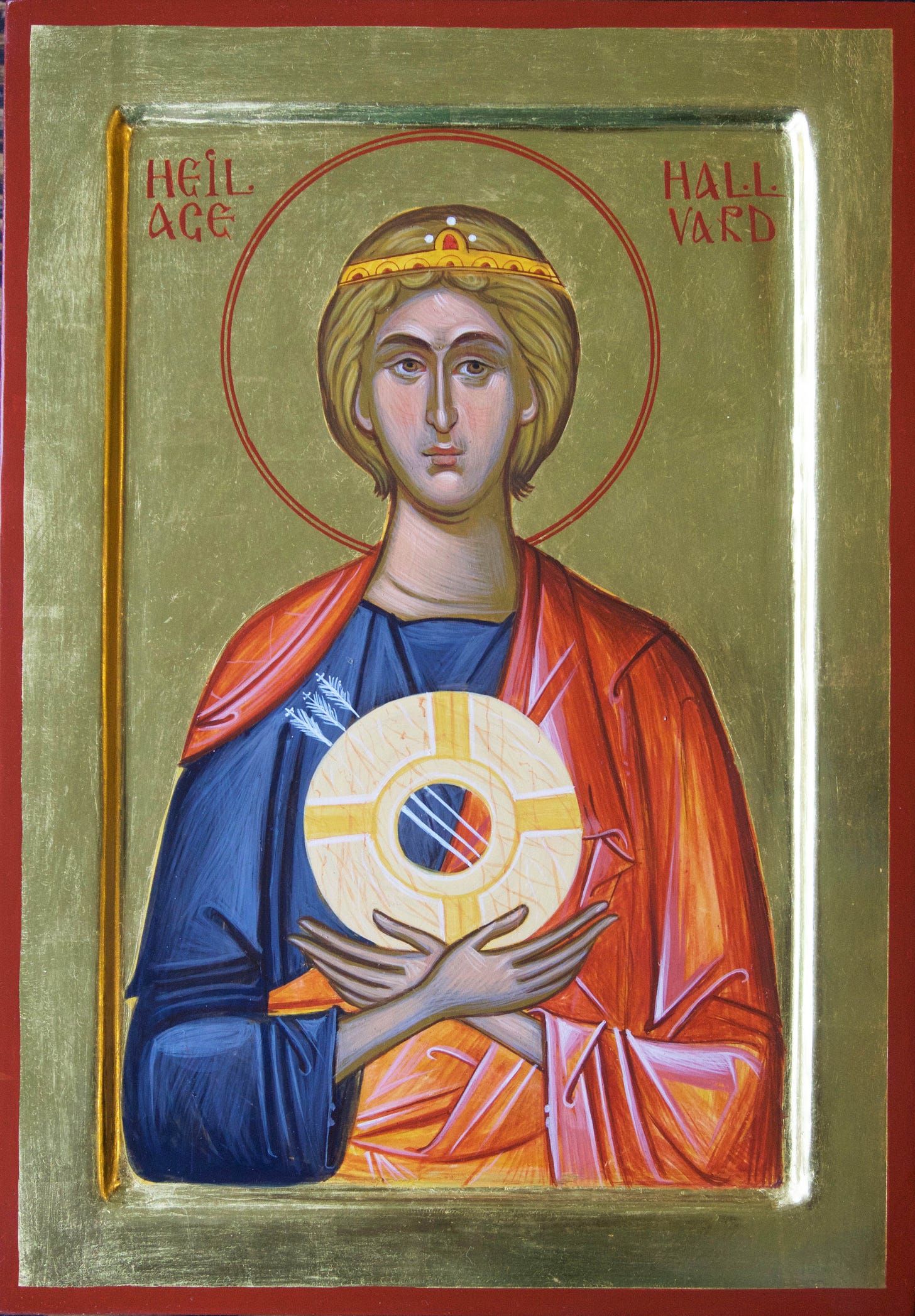

Now the three men on the shore aimed at Hallvard in his little boat. In some versions of the story, they ran up to high ground so they could fire down. In the rain of arrows, Hallvard was killed, as was the woman he was trying to protect and the unborn child within her. That is why in the traditional depictions of Hallvard he is holding three arrows: one for the woman, one for her unborn child, and one for his own life, given for them.

Now that Hallvard was dead, it was easy for the men to swim over and pull his boat back to shore. They buried the woman there. As for Hallvard, they wanted to ensure that the body would not be found, and so they weighted his body down by attaching it by the neck to a millstone, probably taken from a hand-mill. Then they threw Hallvard’s body into the Drammen Fjord.

The men probably did not consider the symbolism of what they were doing, but it was a sad commentary on Christianity which I suspect was not lost on the Christians of the time. Jesus had said that

If any of you put a stumbling block before one of these little ones who believe in me, it would be better for you if a great millstone were hung around your neck and you were thrown into the sea. (Mark 9:42)

Hallvard had set out to be a protector of children. But now he was the one with the millstone around his neck.

But then, in the coming days, something strange was discovered by the men of Lier on the North shore of the Drammen Fjord. It was a body, floating on the waves. Attached to the body’s neck by a rope was a millstone. Strangely, miraculously, those who pulled the body from the sea reported, the millstone was floating too.

The discovery of the body caused a sensation. Who was this man who had been cast into the sea with a millstone around his neck? What did it mean that the very water of the Drammen Fjord had refused to accept the body? Before long the body was identified as that of Hallvard the merchant. The more people inquired about his life, the more they discovered a life of quiet sanctity. Slowly the story was pieced together, and it became clear that a saint had been living among them and would have gone unnoticed if not for his brutal death.

We don’t know what happened to the men who killed Saint Hallvard. We know that the saint’s body was brought to a local church. The locals asked Saint Hallvard to pray for them, and found help and healing. Before long, Saint Hallvard’s memory was spreading, and the body was moved to a larger church in Oslo. Saint Hallvard became the patron saint of the city, one of the great saints of the North.

The iconography of Saint Hallvard emerged. He was drawn as a young man with a halo. He sat on a lion throne to show that he was at least the equal of kings. Before Hallvard the figure of the woman he had tried to save lay on the ground. Saint Hallvard held out his hands, one containing a millstone, and another grasping three arrows.

Time passed, and the story of Saint Hallvard began to fade into symbolism. The Protestant Reformation washed much of it away. People still drew the figure on the throne but they no longer remembered who it was. Was it a person on a lion throne or maybe riding a lion? Maybe it was a woman on the throne and a knight before it. The millstone puzzled artists, who drew it as a ring, or even a snake biting its own tail. In the 19th century, a medievalist remembered what had been forgotten and redrew the old, old image. The city of Oslo has adopted the correct version of the image as its seal today.

Although so though much has been forgotten, we can still catch a glimpse of what Saint Hallvard meant to the men of the 11th century. Only a few decades after Saint Hallvard’s death, his story had come south, to the German chronicler Adam of Bremen. Adam wrote down the name as Alfward, one of two Norwegian saints whose stories he had heard. And so Adam of Bremen told his version of the story:

Alfward, although he long lived a holy life in obscurity among the Norwegians, could not remain hid. While, then, he was protecting an enemy, he was killed by friends. At the resting places of these men [i.e. Hallvard and another saint] great wonders of healing are even today manifested to the people. (Francis Tschan translation)

If you enjoy the Manly Saints Project, please consider signing up for a subscription on Substack, or click here or on the logo below to buy me a beer.