Join me today to meet a king who died a martyr and became his people’s hope.

Name: Eadmund, Edmund

Life: c. 840 - 869 AD

Status: Saint

Feast: November 20

You can listen to this as a podcast on Apple Podcasts, Pocket Casts, Spotify or right here on Substack. If you prefer video, you can also follow on YouTube and Odysee (unfortunately, videos on Odysee may be slower to update).

Even after he had lost the battle, and after his last strategy for stopping the Great Heathen Army had fallen apart, King Edmund refused to compromise. He would not bend the knee and become a client king, serving under the pagan Vikings. He also wasn’t going to take the advice of his surviving lords and flee from his homeland. Edmund had made his play, and through chance and circumstance it had not been a success. Now he waited for the Vikings, surrounded by nothing but a few loyal servants, like the boy who carried and cleaned his weapons and armour.

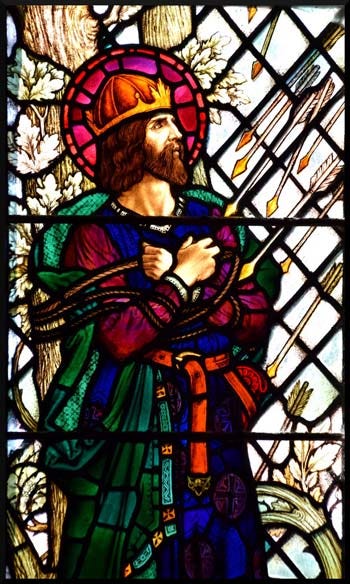

When the Vikings arrived, King Edmund was brought before the war leader, Ivar the Boneless. Edmund’s servants watched as Ivar punished Edmund with a savagery unlike anything they had ever seen. Perhaps Ivar too realized what would have happened if Edmund’s plans had been successful. Or maybe it was something else; one historian has suggested that Ivar wasn’t just killing Edmund, he was sacrificing him. If so, King Edmund wasn’t cooperating. He was beaten and whipped, and called on Christ for strength. The Vikings tied him to a tree and shot arrow after arrow into him, but still, he faintly called on Christ. Finally, Ivar had Edmund untied and decapitated. Ivar knew that these Anglo-Saxon Christians spoke of their bodies rising again at the end of this age of men, this wer-alt, or as we would say world, so Ivar decided to make it difficult for God to put Edmund back together. Ivar had Edmund’s head thrown into the deep forest.

Edmund’s servants looked on in helpless horror. Edmund might not have been broken, but it seemed there would be no Christian burial for this Christian king.

In one way, the story that had come to an end with Edmund’s death had started in 841, the year after Edmund was born. That was the year the first Viking long ships came to East Anglia, a kingdom in the East of modern England, extending inland from the coast to near the modern city of Cambridge.

The pagan people of Scandinavia had been expanding, raiding far from their frozen homelands. The age of the Vikings had arrived. The scholar Alcuin had tried to capture what this meant in a letter to one of England’s many kings :

Lo, it is nearly 350 years that we and our fathers have inhabited this most lovely land, and never before has such terror appeared in Britain as we have now suffered from a pagan race, nor was it thought that such an inroad from the sea could be made. Behold, the church of St Cuthbert spattered with the blood of the priests of God, despoiled of all its ornaments; a place more venerable than air in Britain is given as a prey to pagan peoples. (Whitelock translation)

In 845, when Edmund was still just a toddler, Vikings would raid into the heartland of Europe, attacking Paris in modern France, and Hamburg in Germany. Fifteen years after that, their raids would reach Constantinople, modern Istanbul, the capital city of the Eastern Roman Empire. Since England was an island, it was especially vulnerable to seaborne raiders. Worse, the Viking long ships could operate in shallow water, which meant they could slip into bays and sail up rivers, then vanish before an army could be gathered to confront them.

The men of East Anglia understood the Viking menace only too well, for in truth, their ancestors had used a similar strategy, centuries before. Back then, there had been an Eastern and a Western Roman Empire, but the Western Empire was tottering, losing its grip on what had once been the Province of Britannia. Raiders from the North had flowed in to fill the power vacuum. They had carved out kingdoms with sword and axe, facing local defenders, including, perhaps, the shadowy figure of King Arthur. In East Anglia, Edmund’s family had come to power, and carried the symbol of the great wolf, their ancestor, into their new lands.

East Anglia was a good, defensible place. To the East and South, there was the sea. To the North were marshlands that would be hard for any army to navigate. The real vulnerability were the lands in the West, the passage to the rest of England. Edmund’s ancestors had fortified the area to be able to rebuff attacks that came from that direction. They were safe - providing they maintained control of the sea. And for a long time, they did, remembering the importance of the sea in symbol when they buried their kings in ships, like the man who may be Edmund’s distant ancestor King Raedwald, buried at Sutton Hoo.

By now, the Angles were no longer warlords. Their leaders called themselves Kings - kings of Angle-land. They had adopted the Christian religion, slowly at first and then with enthusiasm. Monasteries and churches were built, preserving their history and identity. The kings no longer claimed to be descended from the wolf, which was now just the symbol of their house. Instead , the family was now claiming a much grander ancestor. They now said they came from a man who had once been a mighty king, somewhere in the distant South. They called him ‘Caser’, that is, Caesar.

Around 855 AD, so tradition has it, the King of East Anglia died. A new king had to be chosen from among the aethelings, the princes, and the choice fell upon Edmund. He was 15 years old. But perhaps the people could already imagine Edmund leading them forward. They crowned him, symbolically, on Christmas Day, an echo of Charles the Great, Charlemagne, who had been crowned on Christmas Day decades before. It was the expression of a hope that, like Charles, Edmund would bring order and security to his people. As it would turn out, he had ten years to do so.

We can see from what would happen next that during his first ten years of peace Edmund must have won the love of his people. All the traditions that offer us details come from long after his time. We hear that he was a godly, Christian monarch. We hear that he was a builder. Meanwhile, elsewhere, events were being set in motion that would bring Ivar the Boneless to England.

In faraway Denmark, a man named Ragnar Lothbrok had come to power, and his sons would form a kind of dynasty. Ragnar brought warriors to the North of England, and for some time he prevailed, but eventually he had been killed, so it was said, by a king in the North. Ragnar’s son, Ivar the Boneless, had sworn revenge. Of course, politics played a role here too. Ivar and others began to gather a massive army, preparing for raiding and conquest in England. They would sail over in a flotilla of long ships, making landfall on the coast of East Anglia.

And so it was that in 865, a huge Viking army materialized off the coast of East Anglia. The scale of the invasion force seems to have taken Edmund by surprise. Edmund scrambled to figure out what to do. No doubt he met with his council, perhaps also consulting with a prince from the nearby kingdom of Wessex, a man named Alfred, who was visiting East Anglia at the time. In the end, Edmund could see no option but to negotiate. He made it possible for the Vikings to spend the winter in East Anglia, and promised to equip them with horses so they could ride North and settle their feud in the spring.

We don’t have any accounts of Edmund’s reasoning, but it’s hard not to see the outlines of a strategy in his decision. The most difficult place to fight the Great Heathen Army, as the Viking invasion force was being called, would be on his coasts. The Great Heathen Army was on dry land now. For Edmund, it was a matter of preparing for war and waiting for the moment to strike. Edmund threw his energy and resources into these preparations, and the effect of his war economy can be seen in the coins his kingdom produced. When Edmund had first reigned, his silver currency was pure silver, now it became mixed with copper, as Edmund tried to stretch every resource to build and prepare.

The opportunity that Edmund seems to have been waiting for came when the Great Heathen Army marched back South. They attacked a city near East Anglia, but in a neighbouring kingdom: Nottingham, in central England, then in the kingdom of Mercia.

In 868, after the Vikings had captured the city, three armies converged on the location, trapping the Vikings in a siege. One army was from Mercia. Another army had come from Wessex, sent by the king of Wessex, one of the brothers of Prince Alfred. The last army, a later tradition has it, was the East Angles, led by King Edmund.

It was a clever plan. The three kingdoms would work together to crush the Great Heathen Army in Mercia. They would fight the Vikings in siege warfare, an unfamiliar kind of fighting where the Vikings would be at their weakest. It could have been the decisive blow. But as the year dragged on, the Vikings managed to hold out. The Mercians became desperate to get the Great Heathen Army out of their land. Finally, the King of Mercia made his own peace with the Great Heathen Army, paying them off, and the Vikings marched back North to wait out the winter.

King Edmund had taken a shot at the Great Heathen Army, and they were looking for revenge. But Edmund had something else up his sleeve. Edmund had maneuvered the Great Heathen Army onto land, and now East Anglia was protected by their fortified Western border. If the Vikings wanted to get back to East Anglia, they would have to break through those fortifications.

Edmund must have sent out his spies to track the Vikings as they came South again. But something went wrong. Perhaps the spies were tricked, or maybe the Vikings moved faster than expected. We don’t know exactly why - the destruction of the English monasteries also meant the destruction of many of the records that might have helped. However it happened, by the time Edmund’s army was raised and in the field, the Vikings had already burst through his Western fortifications, and they were in East Anglia.

We know from the Anglo Saxon Chronicle that Edmund marched his army out anyway. We know they fought fiercely, and we know that, without any of the tactical advantages Edmund had been trying to secure, his army was defeated. The remainder of Edmund’s forces melted away. By the time he was confronted by Ivar the Boneless, Edmund was left with just a few men, civilians or mere boys like his armour bearer. The 29 year old king wouldn’t even consider running away. He intended to make his last stand here, in the home of his people, and face the fury of the Northmen when they arrived.

And so, Edmund was martyred. The Vikings desecrated his body, throwing his head deep into the forest. And in time, the Great Heathen Army moved on. No one knew it yet, but in a few years, Prince Alfred, who had watched the Viking invasions from the court of the martyr king, would rise to become King of the West Saxons. It would be the men of Wessex, under Alfred the Great, who would break the Great Heathen Army. But that was all in the future.

Now, in East Anglia, ordinary people mourned the man they remembered as a saintly king. He had been a father to his people, and now the people came to the place where the body had been left. All they could do was to help Edmund’s few remaining men, like his armour bearer, to look for the king’s head in the forest. They worried that it would have been eaten by animals. But when they found it, they discovered it was intact. An animal seemed to be keeping it safe. It was a great wolf, keeping watch and seeming almost like a guard, though it padded away into the forest when the king’s men came to collect Edmund’s head and prepare his body for burial.

Locals began to come to the place where King Edmund had died to pray, and they found help and healing. The impression he had made was so great that the East Angles kept him on their coins, only now, they called him Saint Edmund, the king.

In the chaotic of the years that followed, Saint Edmund continued to be venerated. Decades later, another future saint, the Bishop Dunstan, would meet the boy who had once polished and prepared Edmund’s weapons. By now the boy was an old, old man, but he could still tell the story of the martyr king. Dunstan would carry the story for years, finally telling it to a visiting scholar, Abbo of Fleury, and it was Abbo who would write the first account of the martyrdom of Saint Edmund.

One of the questions that runs through Abbo’s account is why the martyrdom of the king had brought so much hope to the land of East Anglia. After all, Edmund had failed and he had fallen. To understand the answer, Abbo thought, you had to realize that when Edmund’s body was moved, it was found to be incorrupt. This is actually a fairly common miracle in the history of the Church. But for the people of East Anglia, and indeed the people of England, the preservation of Saint Edmund’s body was not just any miracle.

All over England, people were wondering whether, after 350 years, their civilization had come to an end. They knew how barbarians overthrew civilizations; once they had been the barbarians. Now it was happening again. Was this the inevitable fate of all civilizations, to be destroyed by barbarians incapable of understanding what they were tearing down? Maybe. The wisdom of the North said that a man dies but his reputation lives on. But as the monasteries burned, not only the reputations but even the names of the great men of the past were being forgotten. And yet here, in the incorrupt body of the martyr king, was the promise of another kind of immortality. It was a promise that God would not forget His servants, that He would remember them, even if no one else did, and at the end of the age, they would rise again.

If you enjoy the Manly Saints Project, please consider signing up for a subscription on Substack, or click here or on the logo below to buy me a beer.

Finally checked out the podcast and it’s extremely well done.

May God grant us all just a little of Edmund’s courage.