Join me today to meet a saint who led the Church as everything was falling apart.

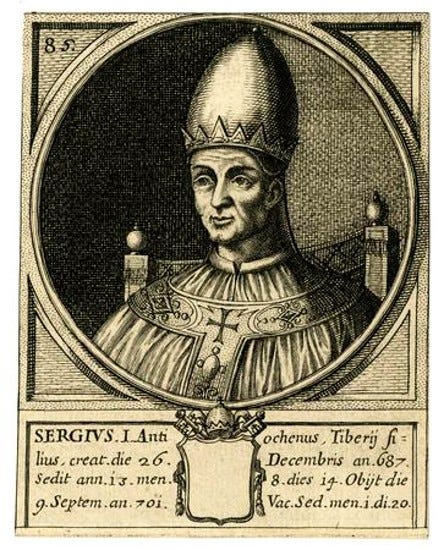

Name: Sergius, Pope Sergius I

Life: c. 650 - 701 AD

Status: Saint

Feast: September 8

You can listen to this as a podcast on Apple Podcasts, Pocket Casts, Spotify or right here on Substack. If you prefer video, you can also follow on YouTube and Odysee (unfortunately, videos on Odysee may be slower to update).

The crack troops of Justinian II, the Byzantine Roman Emperor, had struck too fast and too hard for anyone to stop them. They had burst into Rome, brushing aside city and church guards. No wonder, for the man leading the expedition was Zachary, the emperor’s Protospatharius or First Swordsman. This was a rank among the imperial bodyguard, but Zachary was no mere thug, and in his time protospatharius was becoming a politically powerful position as well. Now Protospatharius Zachary had marched into the Pope’s apartments. Pope Sergius I had no choice but to prepare to be dragged off to the Byzantine capital of Constantinople, to face whatever trial or punishment the furious emperor had in store for him.

It was all because Pope Sergius refused to sign off on the Quinisext. The Quinisext - which you might translate as the Fifth-and-sixth - was Emperor Justinian II’s brainchild. He thought the Fifth Ecumenical Council and the Sixth Ecumenical Council had failed to produce enough concrete decisions. So he had called a council he called the Fifth-and-sixth, the Quinisext, to return to the topics previously discussed and this time produce results.

And the Quinisext had produced results. There were lots of findings enshrining the right of priests of the Eastern rites to be married. There was a prohibition on depicting Jesus as a lamb - wasn’t it wrong to depict God as any kind of animal? And most importantly for Justinian II, the Quinisext was to change the distribution of power in the Church to reflect the new political reality. Sure, Saint Peter had gone to Rome. But that had been a long time ago. The Western Roman empire had fallen, and the Byzantine Emperor’s governor for Italy didn’t even live in Rome, he lived in Ravenna, up in the North East. So it was sort of crazy to have the Church centered in Rome when nothing else was. The Quinisext proposed, therefore, that the Church should have two leaders, and the Patriarch of Constantinople would now be on the same level as the Bishop of Rome.

The Quinisext had been been signed by those who attended. Justinian II had also managed to trick or intimidate some clergy who were supposed to be the envoys of the Pope into signing as well. But Justinian recognized that he’d need the Pope’s signature on the document if it was to count for anything.

When Pope Sergius saw the Quinisext, he absolutely refused to sign it. Sergius was the successor of Peter. He had no intention of signing away this responsibility. He had told Justinian that he would rather die than sign off on the Quinisext. Justinian seemed to be willing to let him do so. And so Justinian had sent his crack team of soldiers led by the Protospatharius Zachary to show Pope Sergius I what happened to those who dared to defy the emperor.

Pope Sergius I was used to seeing things fall apart around him. He had been watching it happen for much of his life. His family had come to Rome from the East, probably running from the Islamic conquest, from Syria to Sicily, then as the Muslims began to attack Sicily, to the city of Rome. Young Sergius turned out to have a gift for musical composition as well as a priestly vocation. He entered the Church and slowly began to gain seniority.

Sergius was a good priest. He doesn’t seem to have been a very good social climber. And so he was assigned as parish priest to one of the poorest churches in Rome. Part of the problem was that Sergius was old-fashioned. Once upon a time the Christians had worshipped underground, in Rome’s catacombs, and for a while priests had continued to worship there. No modern priest did that anymore. But Sergius liked it in the catacombs, and liked to say Mass in the dark and stillness surrounded by the silent witness of the martyrs. And so when Pope Conon died in 687 AD, Sergius was far too unfashionable to make the short list for the Pope’s replacement.

And Sergius might have continued his career as an unknown, old-fashioned priest, except that after the death of Pope Conon, things got a little out of hand.

There was a scramble to become pope. A man named Pascal had been planning to become pope for years, scheming and preparing for the day his chance would come. Pascal was an unpleasant character who was known to dabble in magic, and he hadn’t won over as many allies as he wanted. So he bribed the Byzantine Exarch of Ravenna - the governor of all of Italy - to take his side. After the death of Conon, the Exarch suddenly showed up in Rome, demanding that Pascal be made Pope.

Perhaps in reaction to all this, immediately after Pope Conon died, another man named Theodore was hailed as pope by others in the Church.

Soon there were camps. Theodore and his party occupied the central parts of the Papal Palace. Pascal and his men were banging on the doors and threatening them. It was a disgraceful situation. And as other churchmen in Rome watched, they wondered whether either candidate was right. Someone floated the name of Sergius. Oddly enough, despite not keeping up with the latest liturgical fads, he was popular. A delegation to install Sergius set out, and people began to join in. By the time they arrived at the Papal Palace, the numbers spoke for themselves. One of the candidates for pope, Theodore, recognized something in Sergius and immediately told his followers that Sergius was, in fact, the true pope. Pascal was less willing to give up his bid for power, but his ally the Exarch of Ravenna looked at the crowds supporting Sergius and abandoned Pascal. And so, in this undignified way, Sergius I became Pope.

Sergius I was now the head of the Church. But the Church he was leading seemed to be in trouble. Sergius’ family had fled the armies of Islam. Now Sergius looked out at a world where Islam was prevailing. The Roman Middle East was falling to Islam. There were pockets of resistance, for example the group led by Saint John Maron. But then they were betrayed by the Emperor Justinian II, and the Muslim tide all but cut them off from the Church. By the time the crusaders arrived in the Holy Land centuries later, many Europeans had forgotten all about the isolated followers of Maron, the Maronites.

For a long time, Roman Africa had been a source of strength for the Church, producing great minds like Saint Augustine and Saint Cyprian. Now Africa was falling, city by city. There were rumours of a Byzantine lord who was holding out for a time, but mostly bad news came from Africa. Egypt had fallen in the 640s, cutting off the Coptic Christians from the rest of the Church. By 698, Saint Cyprian’s home of Carthage had fallen. And there seemed to be little stopping the invaders from moving West, across the coast of North Africa. And then what would stop them from coming North into Spain?

Even closer to home there was conflict. Parts of Italy were in schism, a remnant of an old struggle for control. And in the East, the Byzantine Emperor seemed to be preparing to break with Rome. If Pope Sergius I ever imagined the Church as it had been at the end of antiquity as a circle of lights around the Mediterranean, now those lights seemed to be blinking out, one by one. From Rome, all Sergius could do was pray for the far flung members of the Church. And I wonder whether that sense of the encroaching darkness was why Sergius reacted the way he did when in 688 he received an unexpected visit from a king.

The king had come from very, very far away, from Wessex, the land of the West Saxons on the island of England. The king’s name was Caedwalla. He wasn’t fleeing anything. Over in Wessex, his victories were won and his enemies lay crushed before him, but Caedwalla had been listening to the priest, the future Saint Wilibrod, and now Caedwalla desired to see the city of Rome and be baptized there. And the message that Caedwalla brought, though he may not have realized it himself, was one of hope. Darkness might be falling on some parts of the Church, but in other parts of the world, the morning light was breaking through.

Pope Sergius I, deeply moved, gave King Caedwalla the baptismal name of Peter.

Sergius looked North and West, and the more he looked, the more hope he saw. He learned that other Saxon kings had hoped to make the pilgrimage to Rome before Caedwalla, and indeed the Saxons had already had saintly kings of their own, like Saint Oswald Whiteblade. There were also men of great learning in the North, like the monk and future Saint Bede, whom Sergius tried to meet - though we do not know whether he was successful. Near the Saxons on Continental Europe, along the coast of the North Sea, lived the Frisians, and Sergius poured his energy into bringing them to Christianity.

And even if Sergius could do little to help the Church in Africa or the Middle East, he could do things locally. Sergius wasn’t a cynic. He worked away quietly, sincerely, trying to make things better, trying to help and lead the Church wherever he could. He worked to fix the rift in Italy, healing the schism in the Northeast. Sergius wanted to help, and kept an open mind. He even listened to some nobles with a bizarre scheme to build a city on stilts in a lagoon off the Northeast coast of Italy. He gave them his blessing.

And so it was that Sergius was supporting the Church where it was growing, sustaining it in Italy, and praying for it where it was under attack, when the Emperor Justinian II organized the Quinisext Council in 692, and then tried to get the Pope to sign the document it had produced. Sergius refused and things escalated quickly. Around 693 the Emperor sent his Protospatharius Zachary leading a force of picked men to go to Rome.

Sergius had no army of his own. Nothing stopped Protospatharius Zachary as he arrested the Pope, and began to make plans to take him to Constantinople. But then Zachary made a mistake. Since he was in control of the city, he paused as he figured out how they were going to go back to Constantinople. Zachary may have assumed that being in custody would make the Pope give up right there. But Sergius had meant what he had said: he would not compromise his office, and he was willing to die if necessary.

As it happened, however, Sergius didn’t need to wait long, because an army appeared in front of the city.

Where had it come from? There was no simple answer to that question. The army was composed of the people of Italy. These were the people whom the Pope had helped, through prayer and negotiation and by indulging the wild schemes of the men who wanted to build Venice out in the lagoon. They had heard that the Emperor was trying to arrest the Pope. And the result had been that thousands of ordinary people marched down from the Northeast of Italy. The people had come to the Pope’s rescue, and they were furious.

The Byzantine Emperor’s men tried to close the gates of Rome, but they were too heavily outnumbered. The army that had come to rescue the Pope was poorly organized. Their military objective was not well defined, but it came down to two main goals: save the Pope, and/or massacre every single Byzantine they could find in Rome. Representatives of the army burst into the Papal Palace planning to do both things if possible. Sergius was still in his rooms, and told Protospatharius Zachary to conceal himself under the bed while he talked down the crowd.

In the end, Sergius managed to avert a general massacre of the Byzantines. He did allow the army to remove the Byzantines from the city, and Zachary and his men were sent on their way alive if a little roughed up on the way out.

Pope Sergius I would be left to complete his pontificate. And in his quiet way, he picked up on another misguided detail of the Quinisext. The document said that it was wrong to present Jesus as a lamb. The argument was good, in a way. How could any animal represent God? The problem was that representing Jesus as a lamb wasn’t Sergius’ idea. It wasn’t anything recent. It was John the Baptist, greatest of the prophets, who had seen Jesus approaching and cried out:

“Behold, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world!” (John 1:29)

Pope Sergius I thought about how to address this misunderstanding. He could write a theological defence. He could make a ruling. But as he thought about it, he realized the situation called for one of his other skills, the skill of composition of words and music. Drawing on this skill, Sergius composed the Agnus Dei. We use his prayer in Mass today.

Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy on us.

Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, have mercy on us.

Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world, grant us peace.

If you enjoy the Manly Saints Project, please consider signing up for a subscription on Substack, or click here or on the logo below to buy me a beer.

WHOA I had no idea that Pope St. Sergius I was so influential for the Agnus Dei prayer in Mass! Praise God! This is such a highlight of reading on Substack.

Now there's somw top-notch Poping. Good stuff, as ever. Keep it up.