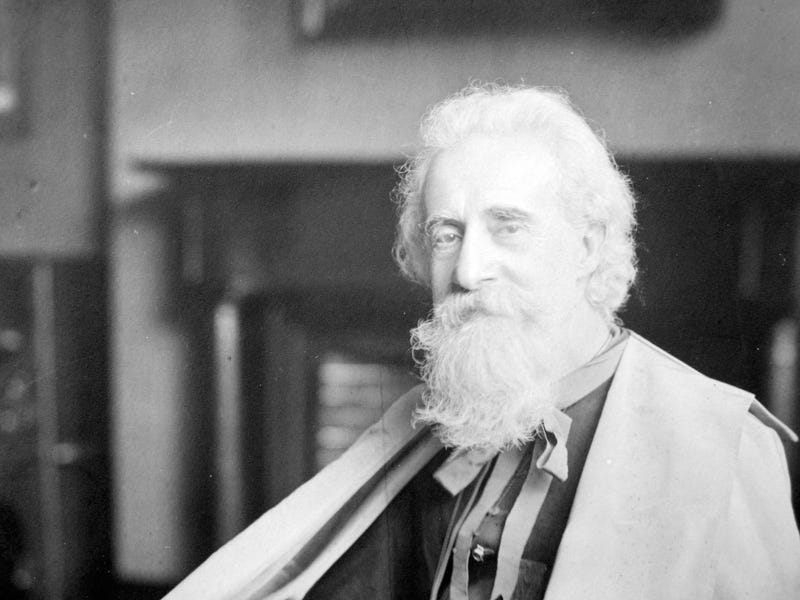

Join me today to meet a martyr who defied the KGB.

Name: Prince Vladimir Ghika, or Ghica

Life: 1873- 1954

Status: Blessed

Feast: May 16

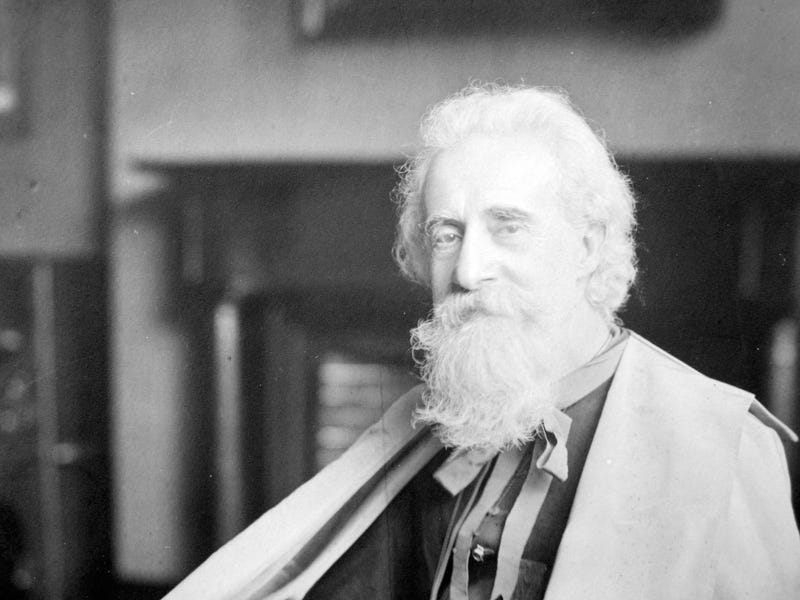

Join me today to meet a martyr who defied the KGB.

Name: Prince Vladimir Ghika, or Ghica

Life: 1873- 1954

Status: Blessed

Feast: May 16