Join me today to meet a blessed for whom becoming a powerful tycoon was only the beginning.

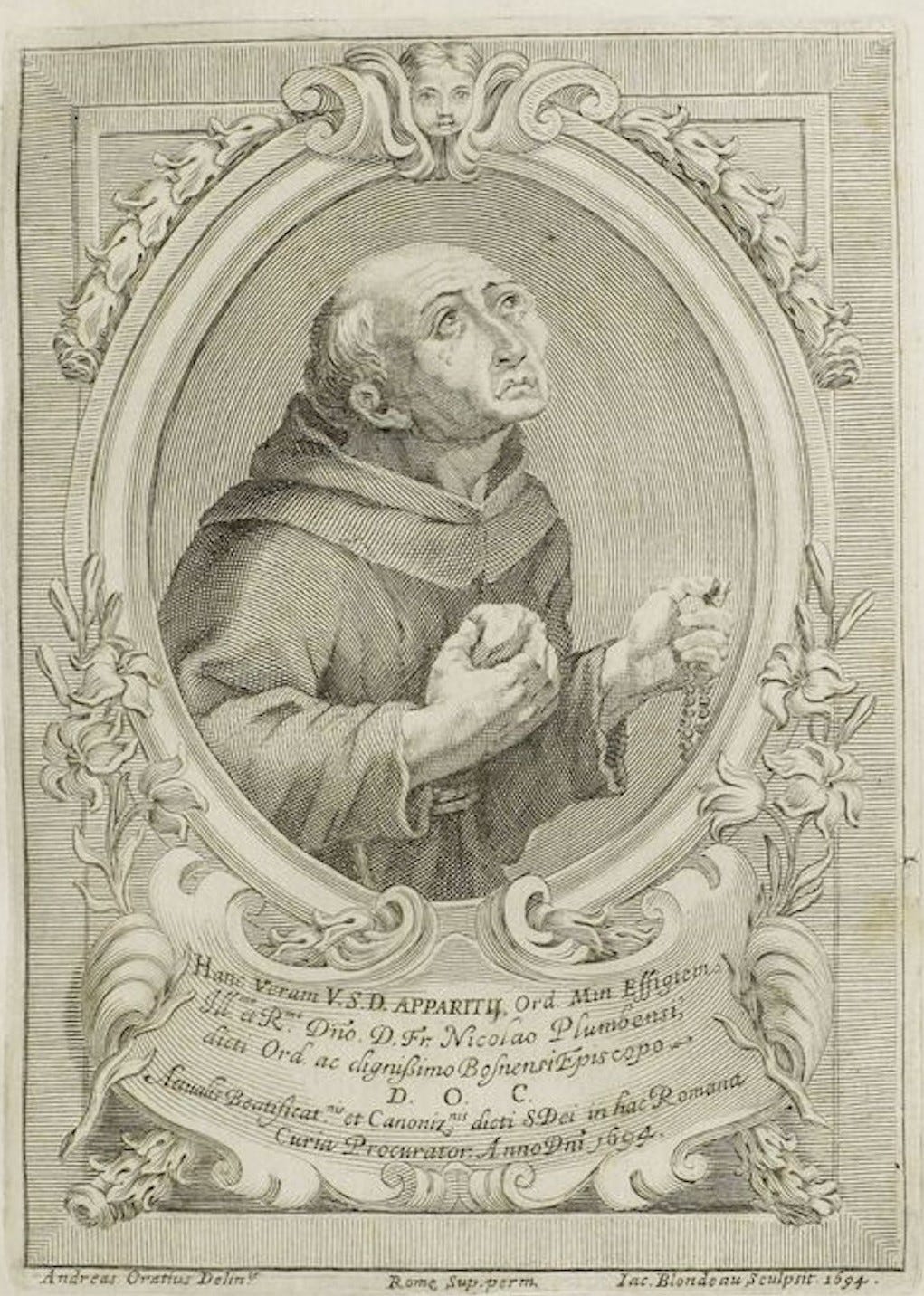

Name: Sebastián de Aparicio, Brother Sebastián

Life: 1502-1600

Status: Blessed

Feast: February 25

You can listen to this as a podcast on Apple Podcasts, Pocket Casts, Spotify or right here on Substack. If you prefer video, you can also follow on YouTube and Odysee (unfortunately, videos on Odysee may be slower to update).

Sebastián de Aparicio was only a boy, and now it seemed that his life was coming to an end. In these first decades of the 16th century, there was an outbreak of plague in Sebastián’s hometown of Gudiña, in the Northwest of Spain. Sebastián had somehow gotten sick, and now the tell-tale symptom of swollen buboes had appeared on the inside of his legs. Sebastián’s parents were peasants, not the sorts of people who could afford medical care. Now their young son was too dangerous to keep at home with his sisters. And so they had led him into the woods to a little shack. Out here, alone, Sebastián would have to fight the disease. All any of them could do was pray. Outside the little shack in the surrounding forest, wolves howled.

After some time, Sebastián began to hear a noise near the shack. Something was circling, sniffing the air. Sebastián realized that the wolves had found him. There must have been a weak spot in the wall, because eventually a wolf forced its way into the little building. Sebastián was too weak to move.

The wolf, though, was behaving strangely. It looked at the angry plague mark on Sebastián’s leg, nibbled at it, then licked the spot. And then the wolf squeezed back out of the shack, leaving Sebastián alone. It was a strange encounter that Sebastián would never forget. Soon, he was feeling better, and he was able to return home. But something had changed. In the shack, alone with the wolf, Sebastián had decided that the rest of his life, however long it might be, would be chaste and lived in service to God.

Sebastián had decided to live in an unusual way, but this was no simple task for a boy from a peasant family. He was not some nobleman who could enter a monastery, confident that his family would be secure. Sebastián’s family needed him. Although he had three older sisters, Sebastián was the only son. And so Sebastián de Aparicio grew up working on the family farm. He started by taking care of the sheep, and was soon running the farm in its entirety.

Sebastián de Aparicio enjoyed the farm work, but his elderly parents needed more support than a small farm income could provide. His sisters needed dowries if they were to find a good match and get married. Aparicio found a job as a servant for a wealthy man. Aparicio had never been to school, and couldn’t read or write, but he was intelligent and resourceful. Soon, he had been promoted to the role of majordomo, running several properties and making them thrive. Now in his 30s, Aparicio had finally made enough money to provide for his parents in their old age. He was also saving to pay for a plan of his own: he had decided to go to the New World.

Ten years before Sebastián de Aparicio was born, Europe had rediscovered the New World of North and South America. Spanish conquistadors had sailed out to explore it, and men like Hernan Cortés and his chaplain, Blessed Bartolomé Olmedo, carved out new territories for Spain. By 1521, Cortés had toppled the blood-soaked Aztec Empire and founded what he called New Spain, in what would become Mexico.

Cortés had founded the port of Veracruz on the East coast of central Mexico only a few years earlier. Since then the fame of Cortés’ exploits had helped the port to grow, and it was already a bustling town. The ship carrying Sebastián de Aparicio sailed into port in 1533.

By the time Aparicio arrived, the Franciscans had been in New Spain for 11 years, having arrived a few years after Cortés victory to relieve the exhausted priest Bartolomé Olmedo. Now the Franciscans found themselves struggling with Cortés’ legacy. Yes, it was thanks to Cortés that their mission was possible in the first place. The problem was that Cortés’ reputation attracted many men from Spain who wanted to be conquerors too. But Cortés had already done that. The Aztecs were defeated. Now New Spain needed men who could build the kind of godly civilization that the conquistadors had promised. The Franciscans had set up a new town where they hoped to model such a society. They named it Puebla de los Ángeles, the city of Angels, modern Puebla in South Central Mexico. Aparicio soon found himself drawn there.

Aparicio’s first instinct was to return to his roots. He tried his hand at farming. But as he looked around, he took stock of what was missing in this New World. The Aztecs had not discovered the use of animals or wheeled vehicles for the transport of goods. Instead, they had a professional corps of porters, the trained tlamemehs who could carry fifty pounds at a jog for fifteen miles every day. Aparicio realized that what was missing was the oldest technology of Europe, the very trademark of the Indo-European people: the ox-drawn cart.

Aparicio turned his attention to breeding oxen. He was the first person to do so in the New World, which perhaps makes him the very first of the cowboys. He found someone to build carts for him and secured the colonial government’s permission to set up a road between Veracruz and Puebla. Soon, Aparicio’s carts were trundling back and forth on a new road between the two towns. When silver deposits were discovered in Zacatecas to the North in 1546, Aparicio built another road and extended his transportation empire. Soon he was a wealthy man.

Aparicio had not forgotten the decision he made alone in the shack with the wolf. He remained chaste. He tried to look at things the way a Christian should, being generous and kind to Spaniards and the peoples of the former Aztec empire. He was so successful in this that his carts could move safely even through the territory of mostly hostile peoples. The more he had, the more he tried to do. Aparicio quietly helped out poor families, or slipped money to fathers who could not afford to provide their daughters with a dowry. In time, he sold his shipping empire and bought several farms. Unlike many wealthy men, Aparicio worked the farms himself, sweating alongside his men and using the work as a teaching opportunity to pass on Spanish farming techniques.

Aparicio was now in middle age, and it seemed to many of his neighbours that a single man in possession of a good fortune, such as Aparicio was, must be in want of a wife. One neighbour invited Aparicio to dinner with his family. It was only after Aparicio arrived that he realized he was going to get the hard sell: the entire extended family had come to badger him into marrying the neighbour’s daughter. Aparicio made excuses, but the family had answers to all his objections. Finally, the only thing Aparicio could think of was a low blow: he told the neighbour he couldn’t possibly marry because he knew the neighbour couldn’t afford a reasonable dowry of 600 pesos. To Aparicio’s horror, the neighbour produced 600 pesos which he had somehow scrounged together for this purpose. In a panic, Aparicio shouted that he’d match it, handed the neighbour 600 pesos, and hurried home.

Still, perhaps the embarrassing event made Aparicio reconsider the question of marriage. He was now in his 60s. Who would inherit his possessions when he died? Aparicio found one poor family who were trying to marry off their young daughter but had no money for a dowry. He asked the girl whether she would be willing to enter into a Josephite marriage, that is, a marriage in which both partners would remain chaste. She agreed. The family also agreed (although they would begin to demand grandchildren almost immediately after the marriage). For his part, Aparicio took comfort in the thought that his young wife would inherit his wealth. He sent her to classes, to give her the education he never had.

But life could end suddenly on the frontiers of the 16th century, and Aparicio’s wife died after only one year. He remarried, another girl from a poor family with the same arrangement (and, as it would turn out, the same family demands for grandchildren). His second marriage was even shorter, and his wife took a fatal fall out of a tree after only eight months. Soon afterwards, Aparicio grew sick himself. There was still no one to inherit his fortune, and he wondered what to do next. He prayed about it, but the answer he received didn’t make sense. He kept thinking he was being called to a religious vocation.

Aparicio, of course, was far too old to be a monk. He was entering into his seventies. His spiritual advisor and his friends persuaded him that at his age he could not endure the life of a Franciscan. Instead, Aparicio’s spiritual director found a compromise. Aparicio donated his fortune to a convent of Poor Clare nuns. He would be allowed to live on the grounds of the convent, serving as a gardener, into his old age.

The trouble was that the religious vocation did not go away. Finally, Aparicio went against the advice of all his friends and persuaded the Franciscans to let him join them. They eventually agreed, getting someone else to sign his vows for him in 1575, since Aparicio remained illiterate. At first, the Franciscans put the new Brother Sebastián de Aparicio to work in the kitchens. Then they found another role for him. He was sent out into the world to ask for alms to support the work of the Franciscans.

Brother Sebastián approached his new role with his usual energy. He found a Catholic farmer who was willing to donate some oxen, and built a cart to go with them. Brother Sebastián took the reins in one hand and held his rosary in the other and set out to go from village to village, asking for alms. At his age, no one expected him to work for very long.

But in fact, Brother Sebastián would raise alms for the Franciscans for the next 25 years.

In time the locals became used to seeing Brother Sebastián, the man who had once been a powerful tycoon but was now a humble friar, trundling through their towns with his cart. The alms were for the Franciscans, though people soon noticed that donations had a habit of falling off the cart when Brother Sebastián passed the poor and needy. In every season, regardless of the weather, the ox cart moved on. At night, Brother Sebastián spread out his cloak under the cart and slept there. There were dangerous animals and hostile peoples, but Brother Sebastián passed quietly along, untroubled.

People began to tell strange stories about the old Franciscan. One farmer promised some grain to the friars, but then had second thoughts. He didn’t want to tell Brother Sebastián no to his face, so he said that the grain was there but he wouldn’t help Brother Sebastián to load it. The farmer was sure the old man would not be able to pile a cart high with sacks of grain, and he was right. What the farmer had not expected was two strong men in white clothing to walk onto his property, heave the grain into the cart, and depart without a word. The farmer, unsure what he had just witnessed, became one of the Brother Sebastián’s greatest advocates.

The ministry went on, Brother Sebastián getting his cart through bad weather and along treacherous roads, always finding a way through. But he was now in his nineties. People were always amazed at Brother Sebastián’s way with animals, the way they seemed to obey him without any effort on his part. The old Franciscan was always willing to help, gently calling people to repentance, sometimes for sins only they and he seemed to know about. If people thought his wandering life lacked purpose, he saw it as a metaphor for the life of a Christian. The key was to push forward, and never lose sight of God.

Brother Sebastián was 98 years old when he grew very sick. He returned to the Franciscan friary, spending the last few days of his life in a bed. He had not slept in a bed for a quarter century. When Brother Sebastián died, the Franciscans intended to put his body on display for a little while before the funeral. They had to keep putting the funeral off, however, as thousands of people whose lives he had touched flocked in to see the body and pray. Reports of miracles through his intercession began coming by the hundreds. Blessed Sebastián de Aparicio had lived such a strange life that it was hard to sum up, but one contemporary put it best. If one could look at the tracks left by the strange, great life of Saint Francis, perhaps within those footprints one might make out a second set of tracks, smaller and lighter maybe, but left by a man walking the same path. This was the trail of Blessed Sebastián de Aparicio.

If you enjoy the Manly Saints Project, please consider signing up for a subscription on Substack, or click here or on the logo below to buy me a beer.

This was delightful storytelling! Charming, beautiful and very Franciscan! Thank you.

A saintly story that inspires.