Join me today to meet the martyr who was the last Roman philosopher.

Name: Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius

Life: c. 480 - 524 AD

Status: Blessed

Feast: October 23

You can listen to this as a podcast on Apple Podcasts, Pocket Casts, Spotify or right here on Substack. If you prefer video, you can also follow on YouTube and Odysee (unfortunately, videos on Odysee may be slower to update).

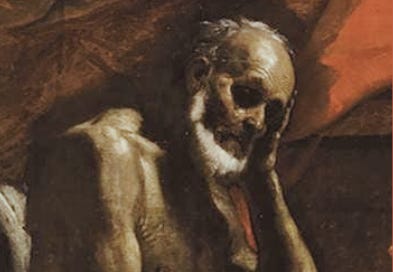

We meet the scholar and philosopher Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius, once Consul of Rome, once the king’s Master of the Offices, in a prison cell in Pavia, in the North of Italy, waiting to die.

Things had changed very fast for Boethius, as we call him today. His fame had carried him to the top. Boethius had turned a critical eye on his own moment, and recognized that there was something terribly wrong with it. He had planned to do what he could. And then the winds of politics had shifted, and everything had fallen apart. Now he was preparing for death, and he was barely into his 40s.

Perhaps Boethius was in an unusually good position to understand the moment he was living in, because his family had been active in Rome for such a long time. He was one of Rome’s Patricians, a member of the Gens Anicia. The Patrician families were said to have been there at the founding of Rome, a thousand years earlier. A republic emerged, governed by two powerful officials called consuls. Much later, when the Roman Republic tore itself apart and rebuilt itself into an empire, the Gens Anicia were there, even occasionally producing emperors. Then, as the empire aged, Christianity emerged from a barely known, persecuted faith to become Rome’s state religion, and the Gens Anicia were there too. One of Boethius’ relatives had been a pope.

The Roman Empire grew so unwieldy that eventually two emperors ruled at the same time, one in the East and one in the West. And around that time, those on the frontiers of the empire began to report disturbing contacts with massive barbarian tribes trying to move West. The tribes were looking for refuge from barbarians who terrified even them, the Huns. Once, Rome’s armies would have marched out to protect their borders. But by this time, Romans were no longer interested in such things. Instead they tried to get the barbarians to fight for Rome. That didn’t work for long, and the balance of power soon shifted toward the barbarians.

In 410 AD, the unthinkable happened. Rome, which had stood for a thousand years, was sacked by a band of Goths, led by King Alaric. No one had quite believed that Rome, the eternal city, could be sacked. But life goes on, and soon the people of the Western Roman Empire got used to living with the risk of barbarian attack. The barbarians who had once been refugees now set up their kingdoms within the territories that had belonged to Rome. In 476, another Goth, Odoacer, threw the last Western emperor out and made himself king in his place.

About four years later, Boethius was born.

Boethius was born a Roman aristocrat - though by now, his title had little meaning outside the city of Rome. When his father died, Boethius was raised by another aristocrat, a scholar who was to become a lifelong friend. He taught young Boethius to read and study. Soon Boethius was taking in the works of the great thinkers of the Greek and Roman past. And as he did, he began to recognize that the Rome he lived was a shadow of what it had once been. Yes, there were still consuls, there was still a Roman senate, but these institutions had little power outside of the city of Rome itself. Once Rome had been the center of the world. Rome no longer seemed to be central. The pope was in Rome, but the Eastern churches were in schism, so papal authority was not what it had been. And as for the new Gothic king, Theoderic, he wasn’t even in Rome, but in the Northeast of modern Italy, in the city of Ravenna.

Boethius looked around and saw decline. It wasn’t just that circumstances had gotten worse. In some ways, the people had declined too. Once Romans had been willing to fight. Once many Romans read Greek for pleasure. Certainly the Romans of the past would never have endured the rule of King Theoderic, who had inherited Odoacer’s holdings through the technique of murdering him at a banquet. Romans of the past wouldn’t have put up with the fact that Theoderic wasn’t an orthodox Christian; the Goths were Arian heretics, although fortunately Theoderic didn’t care about converting the Romans to his views.

Boethius realized that his beloved city, and her people, were fading away into history. What should he do? He was wealthy enough to keep to himself and live a comfortable life. Instead, he formulated a two-part plan.

First, Boethius recognized that Roman culture was slipping away. He was a student of philosophy, which at the time included both reasoning and what we would call natural science. Soon, Boethius figured, hardly anyone would read Greek anymore. Rome’s new barbarian masters would be lucky to understand Latin. Boethius committed himself to the project of translating the great works of philosophy, aiming to translate everything that Aristotle and Plato had written. He didn’t just want to fire out quick translations, either. He wanted his translations to fit together, to standardize terms in a way that would be useful to future readers. Boethius knew that this would be the work of a lifetime, so he started into Aristotle’s logical works, stopping to write out his own thoughts on philosophy and theology as well. After all, he should have plenty of time.

The second part of Boethius’ plan was to make life better for the people he lived with. For that he needed power. And soon, power came to him.

King Theoderic needed a gift for another barbarian king, Gundobad, who had carved out a place for his Burgundians in the Southeast of modern France. Theoderic knew that Romans once built elaborate machines. He asked Boethius if he could figure out how to build such a thing. Boethius provided Theoderic with a waterclock.

Theoderic kept returning to Boethius for help. At first it was the making of old things and cultural questions. But soon the king was asking for help with more practical matters, like investigating a palace official who was paying the king’s bodyguards with debased precious metals. At first, the king thanked Boethius with honours, even making Boethius a consul. Eventually, the king let Boethius’ two sons be consuls together - a gesture Boethius appreciated deeply, even if it showed how empty the title of consul now was.

In time, Theoderic realized Boethius could be more than a cultural advisor. The king offered him a place at court as Master of the Offices, which put him in charge of palace administration and of the entire civil service, including the network of Theoderic’s spies. Boethius would be among the most powerful men of Theoderic’s kingdom.

Now that he was a powerful man, Boethius was finally in a position to start improving the kingdom in a more practical way. Boethius made it his mission to help ordinary people and stamp out corruption. On one occasion, there was a shortage of food. Boethius’ informants told him that despite the food shortage, grain was still being shipped out, it just wasn’t going to those who were hungry. He was outraged. Technically this was the domain of another high official, but Boethius set out to fix things, and accused the other man of not doing his job. The fight got so public that the king took note - and determined that Boethius was in the right.

The trouble was that standing up for the poor made a man enemies. These enemies identified what could be Boethius’ downfall: his attachment to the old institutions of Rome. Now all they needed was a change in the political winds.

The winds changed in 519 AD. Since Boethius had been a little boy, the churches of the East and West had been separated, due to a dispute we remember as the Acacian Schism. A disagreement had put the pope at odds with the patriarch of Constantinople. Shortly before Boethius turned 40, the Acacian Schism was resolved, and the Eastern churches once again recognized the authority of the Pope.

Now the end of the Acacian Schism was bad news for King Theoderic. As an Arian ruling over Catholics, Theoderic always worried a little that his people might prefer a ruler of their own faith. In the past he hadn’t worried too much, since the Eastern and Western churches had been fighting each other. Now that they were united, what would prevent the Eastern Romans from ousting Theoderic? Wouldn’t many faithful Catholics in the West take up their cause?

Just as Theoderic was worrying about this development, a Roman senator wrote a letter to someone in the East. The letter was intercepted - perhaps by Theoderic’s spies. Boethius read it, and though he thought the senator was being incautious, perhaps blowing off steam, Boethius didn’t see it as disloyal to Theoderic. However Boethius’ enemies insisted that the letter had been treason. The senator was plotting against the king, and if Boethius wasn’t willing to see him suffer for it, it must be because Boethius was part of some plot too! Just for good measure, they also accused Boethius of sorcery.

Even a year earlier, Theoderic would probably have supported his Master of the Offices. Now, Theoderic just saw one Catholic supporting another Catholic against him. Boethius was stripped of his honours and sent to Pavia to await the time of execution. He was going to be a martyr.

Boethius sat in Pavia and thought about his life. He had felt pushed, even called to pass on philosophy to those who would come after, in a time when less and less of the great classical past would remain. He thought he would have years. Now, with only months left, it looked like he had failed.

And then Boethius thought of something. Perhaps he was exactly where Providence had placed him. And if so, perhaps he could accomplish some of what he had set out to do, by telling his own story. And so in the days that he had left, Boethius wrote the short book for which he is most famous: The Consolation of Philosophy.

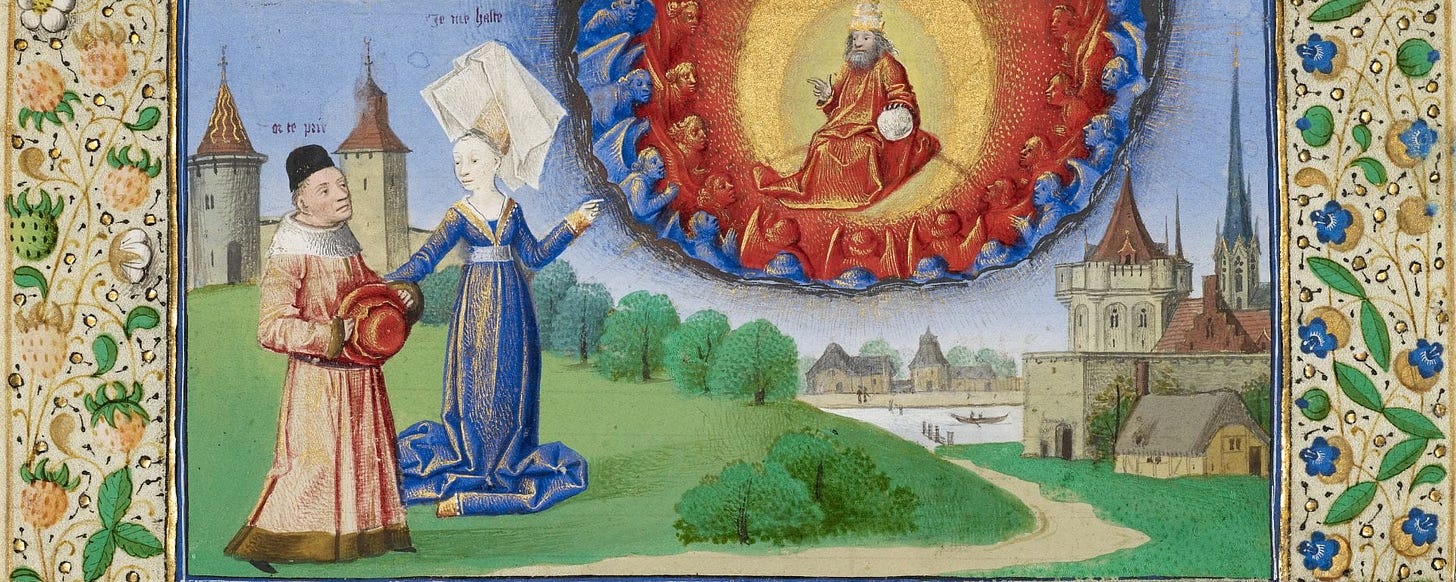

The book opens on Boethius in prison, writing sad poetry about his fate. Soon another character enters the room, a woman who stands for the art that Boethius had pursued his whole life: Lady Philosophy. Boethius is lost in grief and and anger at having his honours snatched away. Lady Philosophy gently peels away the layers of pride and entitlement, pointing out to him that fortune’s symbol is a wheel, and for good reason. You may think you are rising on fortune’s wheel, but the higher you get, the closer you get to the point at which the wheel turns and you start going down. The whole point of philosophy is to avoid the gifts of fortune and seek things that last.

Ancient philosophers had explored ethics by bluntly asking: is it worthwhile to be good, and if so, why? Boethius and Lady Philosophy understand that our lives will be judged, but they lay that aside to consider the old philosophical question. And so in the story, Lady Philosophy explains how virtue is something like health, in that without it nothing else is worth having. Indeed, goodness is a shadow of Goodness, and virtue aligns us with God. It was something Boethius had mentioned in an earlier, theological work, that we seek to imitate Christ in the aligning of our wills to His. Lady Philosophy helps Boethius to understand that even though he has been wronged and put in prison to die, in a paradoxical way, Boethius is still better off than his accusers.

In the story, Boethius still pushes back. But why is the world full of evil? Lady Philosophy responds with a philosophical answer to the problem of evil and a defence of Providence: an order in things that we can recognize but not predict, and one that offers consolation if not always comfort. The story of Boethius’ grief becomes a framework for philosophy, one that takes us through ethics to the metaphysics of a world ordered by Providence. And that is the end of the book.

Soon after writing it, Boethius went to die.

Boethius would be proven right about the future. Rome would not rise again. The barbarian waves would wash over Europe, changing everything. Not many would be able to read Greek, indeed, in some of the new kingdoms, only a few people would be able to read at all. Kings would rise and fall on fortune’s wheel. The Church would collect knowledge in monasteries, waiting for a more stable time. Europe would slumber in what we remember as a dark age.

But even in a dark age, there are lanterns. Boethius had hoped to provide such a lantern for an uncertain future. And it turned out that the work of his that burned brightest was his last. The Consolation of Philosophy wove the story of philosophy into Boethius’ own story, and it spoke to men who faced fortune’s wheel themselves.

As the Frankish people were forging what they would call the Holy Roman Empire, they were reading Boethius. When in England King Alfred the Great held back the pagan Vikings, he took time to translate The Consolation of Philosophy. Boethius contained the seeds of the project of medieval philosophy: to bring together pagan wisdom and Christian revelation, to synthesize faith and reason. And so it was that when Europe emerged into the middle ages, everyone from kings to poets to philosophers had been shaped and moved by the private thoughts of the last Roman philosopher facing the end.

If you enjoy the Manly Saints Project, please consider signing up for a subscription on Substack, or click here or on the logo below to buy me a beer.

I’m really enjoying these. Thank you!

It reminded me of my reading when I was young and now I know who we learned about Aristotle through: Boethius - thank you